Including the Electoral College in your civics and government class is essential. And since it’s a bit complicated, it’s a great topic to spend a few days on because there are so many ways to practice critical thinking and general social studies skills.

Rather than just giving a quick overview of how the Electoral College works, take time to explore its origins, how it affects presidential elections today, and a few of the alternatives available.

I also like to weave it into a larger simulation with the primary/caucus election process. To make it more fun, I use potato chip flavors for the different presidential candidates. You can check out my complete Electoral College Simulation Kit here.

Below are my favorite activities to teach about the Electoral College, including that potato chip simulation game and an in-depth DBQ research project.

But first, here’s a quick background on what it is and why it’s so controversial.

What is the Electoral College?

The Electoral College is how the United States elects its president. Instead of a popular vote, it’s a vote by special electors from each state. These are, in fact, real people who cast their vote in December at their state’s capital. Each state has a certain number of these electors, which is determined by the number of members of Congress it has. Larger states like Texas have dozens, while small states like Wyoming have a minimum of three.

There are 538 electors, and a candidate needs at least 270 electoral votes to win the presidency.

Technically, a vote by the people doesn’t even need to occur. It’s held because the electors are supposed to take in a sense of the people’s wishes, but how bound they are to those results has varied over time and by state.

Crazy, right? The system was chosen because it was a compromise. It allowed both a popular and an elitist vote, which in the late 1700s was already a never-done-before step towards representative democracy. It also allowed smaller states to have some say alongside larger ones. Founders at the time knew it was a more complicated option, but they were dedicated to trying out democracy.

Why is the Electoral College so Controversial?

Perhaps even crazier is that someone can win the Electoral College vote but not the popular vote. In one way, this was intentional, as the Framers wanted to prevent harmful people from being elected by the “uneducated” masses. However, states choose to allot their electoral votes using an all-or-nothing method, which can also create that outcome.

This has happened five times in US history, twice in the last 25 years—the 2000 and 2016 elections. In 2016, three million more people voted for Hillary Clinton than Donald Trump. However, Trump won the right combination of states and thus won the Electoral College vote.

This has fueled debates about whether to replace or revise the Electoral College. On one hand, the Electoral College forces candidates to campaign across the states, not just highly populated cities. On the other hand, critics argue that votes in some states “count” more than others.

There are multiple alternatives to how the Electoral College currently works, each with pros and cons.

Activity Ideas for Teaching the Electoral College

Even though the Electoral College only meets once every four years, you should absolutely be teaching about it yearly. I put it in my Voting & Election unit during presidential election years. For the other three years, I teach it within my Executive Branch unit.

I’ll spend at least a few days on it simply because there is so much you can do with this topic. Below are some of my favorite lessons to do.

1. Use Explainer Videos

Before diving in, this is a great topic for students to do a quick brain dump on. They all know something, have some opinion, or have heard something about it, but they likely also have many gaps in their understanding.

Then, give a quick lecture or show some explainer videos for a broad overview with some visuals.

Some great videos to use: TED-Ed’s Does Your Vote Count?, CBS’s The Electoral College Explained, or Vox’s The Electoral College, Explained.

After watching, have students revisit their brain dumps to revise what they wrote and then form a few more questions based on what they learned.

2. Analyze Federalist Papers

The Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers can be intimidating, but in small doses, they’re fantastic for exploring specific Constitutional issues. This is a perfect example.

We have two opposing essays focusing on the proposed Electoral College system. Pull a short excerpt from each for students to read through and analyze their arguments.

Here’s the excerpt from Federalist 68 that I like to use:

It was desirable that the sense of the people should operate in the choice of the person to whom so important a trust was to be confided. It was equally desirable, that the immediate election should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station,…

A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.

[This] process of election affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.

Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union, or of so considerable a portion of it as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States.

And this excerpt Anti-Federalist essay No. 72, written under the pen name Republicus:

Is it necessary, that a free people should first resign their right of suffrage into hands besides their own. And, after all to intrust Congress with the final decision at last?

Is it necessary, is it rational, that the sacred rights of mankind should thus dwindle down to Electors of electors, and those again electors of other electors? This seems degrade them even below the prophetical curse denounced by the good old patriarch…

To conclude, I can think of but one source of right to government and that is THE PEOPLE. They, and only they, have a right to determine whether they will make laws, or execute them, or do both in a collective body, or by a delegated authority.

Therefore if any people are subjected to an authority which they have not thus actually chosen-even though they may have tamely submitted to it-yet it is not their legitimate government.

After reason, ask your students questions like:

What were some of the founders’ fears about holding a popular vote?

Are these fears still true today? Why or why not?

Who makes the most compelling argument?

3. Examine Modern Data & Political Cartoons

Pull together some graphics of the Electoral College for students to analyze in small groups or stations.

These are my go-to ones:

Election result maps from the last few elections. The website 270towin.com is excellent to use in an election year. Wikipedia entries for each election contain several graphs of results for all sorts of comparisons. For example, the 2024 presidential election.

PoliticalCartoons.com is great for cartoons on any topic, so search for the Electoral College. For an easy protocol for analyzing cartoons, grab my free Political Cartoon Kit.

The Pew Research Center is a fantastic non-partisan think tank that polls Americans on various topics and displays their findings in easy-to-understand graphs. Here are their findings on Americans’ opinions on the Electoral College.

4. Run an Electoral College Simulation

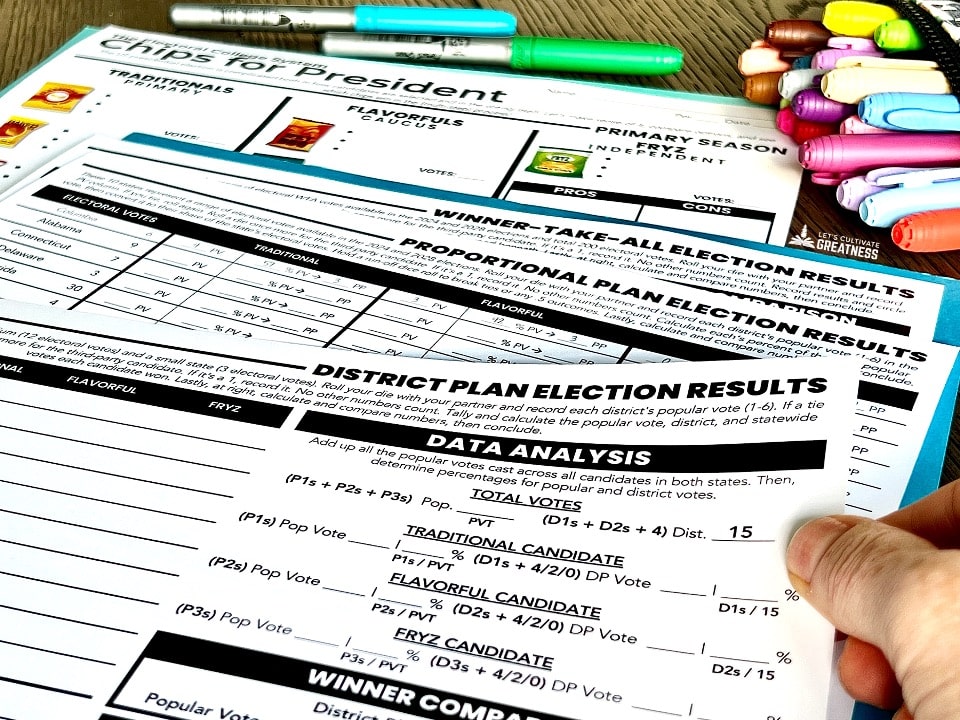

Once students understand how the system and “winner-take-all” method work, they are ready to see it in action. With some dice and a list of each state’s electoral votes number, pair up students to “race to 270” against each other.

I also like to simulate a few other counting methods for students so they can really see how each method has its pros and cons.

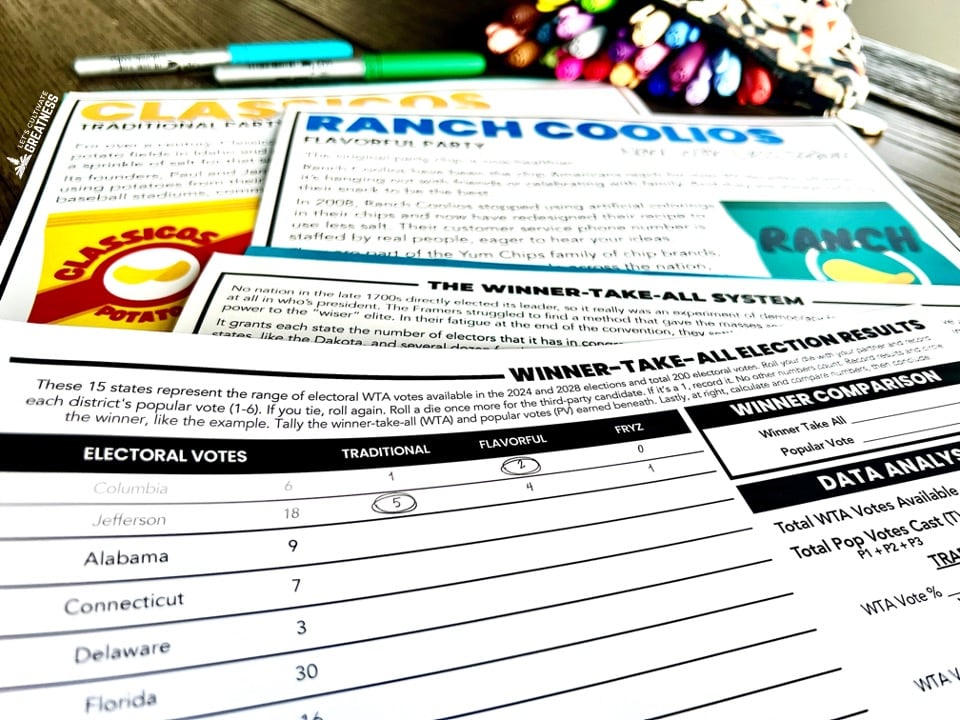

We use potato chip flavors for the candidates and political parties, which adds a fun element without detracting from their critical thinking. And it focuses on the process rather than the real-life candidates.

After playing the dice game for the winner-take-all method, we do it with the district and proportional counting methods. These go quickly. Then, students get to enjoy some potato chips! Click here for your own done-for-you kit of this fun activity.

5. Research Alternative to the Electoral College

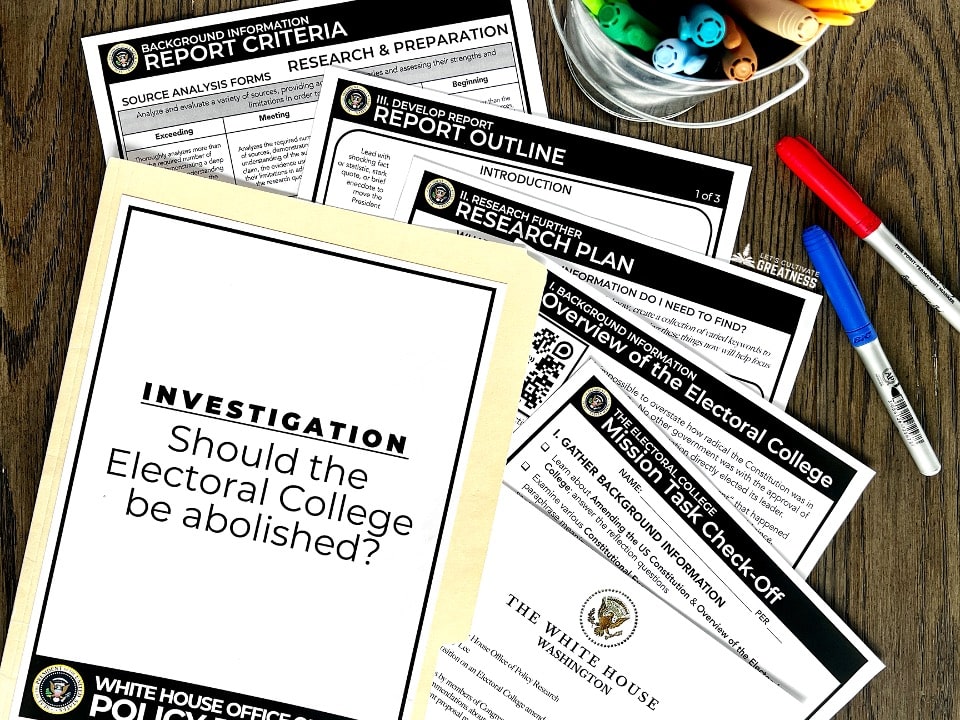

If you have an advanced group or a bit more time, this is the perfect topic for a DBQ-style research essay. I use this as one of the topic options I give students for our end-of-semester project.

Gather all those sources, including the Federalist excerpts, maps, polling data, political cartoons, and students’ own simulation experiences. Have students use them to argue whether the Electoral College should remain in place, use one of the alternative counting methods, or be entirely replaced with a popular vote.

Students have strong opinions, so they are pretty invested in deciding for themselves the best way to elect the President of the United States.

You can check out this complete PBL-style project here.

Want these activities and more to bring into your Civics class? Grab my Executive Branch unit or Voting & Elections unit for all sorts of projects and activities.

Feature image photo credit: The meeting of electors for Washington State to cast their ballots in the 2020 presidential election. Governor Jay Inslee and Secretary of State Kim Wyman are standing in front. (Washington State Archives)