For the vast majority of us, our high school history and social studies classes involved either a lot of memorization, a lot of movies, or both. Either way, they didn’t involve a lot of wondering, investigation, grey area, or multiple right answers.

Now we know these things are the core of teaching these courses well. Thank goodness! Unfortunately, however, so many of the inquiry-based learning models out there feel too idealistic and impractical to implement in a real classroom.

If history and the social sciences are naturally intriguing (because, really—why do we do what we do as humans, right?), then it doesn’t seem right to me that we should be overcomplicating it.

So let’s break down building your first inquiry-based unit into a handful of clear, doable steps with some examples to boot!Then, once you’re ready to move on to creating your assessment, check out my guide on teaching scaffolded social studies writing, which picks up where this post ends.

Here are the 5 steps you need to create your first, great inquiry-based social studies unit.

1. Decide your inquiry unit’s central concept

2. Write your inquiry unit’s central question

3. Focus learning with a graphic organizer

4. Find a variety of primary sources

5. Tie every activity to your inquiry question

1. Decide your inquiry unit’s central concept

The first step in transforming your unit to be inquiry-based is deciding the central concept. This functions as your focus for the entire unit. It should be abstract, but something students have incoming understanding of regardless of their ability level. If you must define it for them, it’s not a good central concept.

This central concept is crucial because in inquiry-based learning, you want to laser-focus students on one thing.

For example, transform your Gilded Age unit by focusing on the innovations and advancements made, using “opportunity” as your central concept. If you want the focus more instead on the role of government at the time, then a concept like “laissez-faire” or “welfare” (à la U.S. Constitution Preamble) would make more sense.

If needed, it’s better to form two or three mini units to cover a large era, each with its own focus, rather than trying to cover too many concepts all as part of one unit.

Notice the central concept is not the unit’s topic. The topic in a history class is the historical era.

In Civics, your unit topics are usually things like Principles of the Constitution, Elections and Political Parties, or Three Branches of Government. But your central concepts for those units could be “democracy,” “voting,” and “representation,” respectively (at least, those are the ones I use for my units!)

This distinction matters because it will forge the decision making for the rest of your unit planning.

2. Write your inquiry unit’s central question

Once you have a clear central concept, your unit’s driving inquiry question will almost write itself. That’s because you’ve already determined your intended takeaway—you just didn’t realize it!

Take our Gilded Age unit, for example. If you want to focus on “opportunity” then you already decided that you want students to grapple with the unimaginable wealth and poverty that existed simultaneously.

The two most important things to remember about great inquiry questions are:

They need to be short and easy-to-understand from the first day of the unit. Your kids may not know the answer to the question on day 1, but they should understand what it’s asking. If you’re having to unpack the question, then it needs to be simplified.

They don’t have a single right answer. Both sides should be equally arguable. However, be careful to not have a question that lets a student argue against something that’s non-negotiable, like the dignity and basic rights of all people. For example, avoid questions that ask students if westward expansion was inevitable or justifiable, which can dismiss the devastation that occurred to tribes living on those lands.

With those two rules in mind, your Gilded Age question could be, “Was late 1800s America the land of opportunity?” Short and simple to ask; complex and nuanced to answer.

Here are some other examples from across my various classes:

US History: “What makes an American hero?” from my American Hero thematic unit

Civics: “How are my Constitutional rights decided?” from my Bill of Rights unit

Global Issues: “Am I in the majority or minority of the world’s population?” from my World Population and Poverty unit

3. Focus learning with a graphic organizer

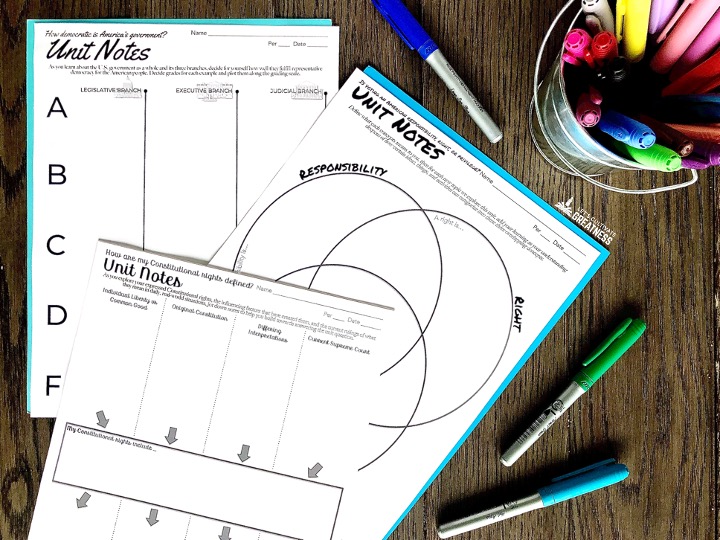

Next, determine what kind of mental organization your question is requiring students to do. If it’s a this-or-that with two sides, then a T-chart is your go-to. If it’s a comparison, then a Venn diagram. If it’s a “how much” gradient question, then you need to use a continuum line. If it’s a cause/effect, then an input and output flow chart is what you need.

Create a single-sheet graphic organizer for students to add quick bullet-point notes after each activity throughout your unit. Coming back to our Gilded Age question, students would fill in a T-chart with columns labeled “opportunity” and “hardship.”

4. Find a variety of primary sources

With your graphic organizer decided, it should be clear what sorts of topics students will need to examine. Now you just need to go hunting for your sources.

Continuing with the Gilded Age unit as an example, your sources could include photographs of Vanderbilt mansions, an excerpt of Andrew Carnegie’s “Gospel of Wealth” essay, Currier and Ives illustrations of technological advancements, political cartoons criticizing the wealthy, narratives of immigrants excited to be Americans, Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine photographs, data charts about income levels—so many options!

The idea is that you pull together a collection of sources that support all the sides of the inquiry question.

If you want to focus on a particular skill with this unit, too, say analyzing political cartoons or writing analytical sentences, then be sure you choose sources to support that work.

For example, in my Foundations of American Values unit, we explore 1800s activists’ writings and art for their use of persuasive appeal.

So I incorporate a few examples each from the abolition, labor, and women’s rights movements, as well as from tribal leaders resisting their people’s removal. Then with the sources, we also analyze them for their use of persuasive devices.

5. Tie every activity to your inquiry question

The strongest way to do this is with students highlighting and annotating their work after they’ve finished exploring it.

For the Gilded Age example, dedicate one color as “opportunity,” and one as “hardship.” Then have your students cover that presidential speech, their notes from a movie clip, or the collection of data charts and photograph they examined in those two colors.

Next is when that graphic organizer comes into play. Make the final step of any activity be adding a few examples from it to the unit graphic organizer. By the end of the unit, your students will literally see their thinking about everything covered and be able to quickly develop their personal position on the unit’s no-right-answer inquiry question.

For example, in my Three Branches of Government unit, we highlight everything in three colors: “very,” “sort of,” and “not really” to work towards answering the question, “How democratic is America’s government?”

Our graphic organizer is a grading scale continuum line that we add to as we go with very short bullet points of things learned, like “two four-year terms for President” or “Senate filibuster rule.”

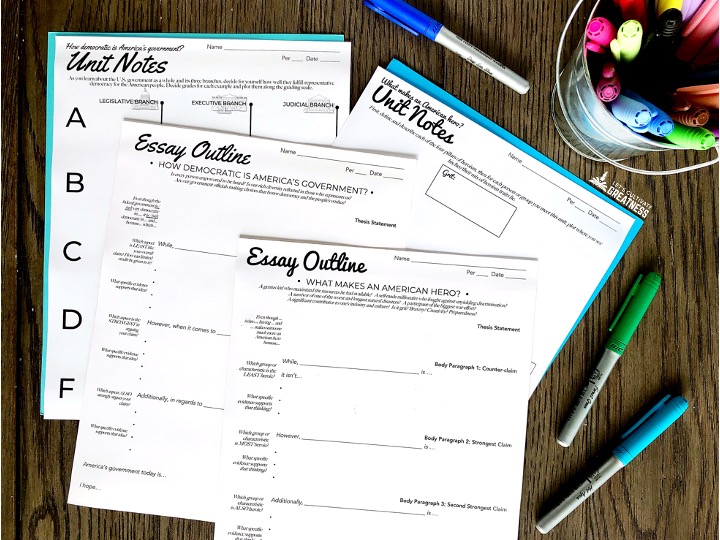

This work done during the unit makes the end-of-unit heavy thinking go so much more smoothly. Students can more quickly form their positions and outline their essays, leading to much stronger writing. This is especially crucial for students who need extra scaffolding.

To learn how to best support your social studies students in writing formal essays, check out my blog post How to Scaffold Social Studies Essay Writing Like a Pro. It continues where this post leaves off, and gives you an overview of my favorite class period—Essay outlining day!

Feature image credit: The Rising Engineer via Pexels.com