You are committed to switching to thematically teaching your history class, you’ve read my blog post of the 5 steps to building a thematic unit, you have a unit and theme picked, your inquiry question is written and activities brainstormed, now how do you actually start crafting the individual inquiry lessons?

Welcome! You’re in the right place. Below, I’ll walk you through the crucial aspects your lessons need in order to build a thriving inquiry-driven thematic unit.

A thematic unit is only as strong as how tightly each activity is tied to the central theme and inquiry. This means every single lesson must connect meaningfully and deliberately.

If you keep this in mind, it becomes easier to decide which activities to include, as well as how you’ll angle them to fit within the inquiry.

Swapping a chronological for a thematic approach can be hard to get your head around. So I included several examples from my own U.S. History thematic units to give you a stronger foundation for building your first unit.

I want to make two quick notes, though, before we get started. One: if you teach civics or any other social studies course, all these same tips work to transform them as well. Two: I use the term subtopic to refer to a 2-4 class period lesson series that deep dives into a specific topic under the umbrella of a unit. I recommend you have 3-5 subtopics in your thematic unit.

So if you are ready to start building inquiry lessons, or convert your existing non-inquiry ones to be master-level effective in a thematic unit, here are 5 must-do’s:

1. Lead with the unit inquiry question

That overarching unit inquiry question should be everywhere. And I mean everywhere.

It’s on my whiteboard, my agenda slide each day, and the top of every single handout. When I’m feeling extra, I have a bulletin board display related to the current unit’s question. And I talk about it constantly.

At the start of each new subtopic in a unit, lead with a reconnect to the unit’s overall inquiry question. Talk about how you have partially answered it so far, how you still need to answer other parts of it, and how this next subtopic will help answer the question.

For example, in my Founding Values unit, which is our colonial to late 1800s starter unit, our question is “Who really founded America’s values?” and it asks my students to analyze the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution preamble against the arguments of early American activists.

Within that unit, we use a framework of FORE values (freedom, opportunity, representation, and equality) with each value serving as a subtopic. To kick off each value, we refresh on the founding documents and how that value is present. Next, we dive into learning about the activists and the impact of their arguments.

Action item: Put your unit inquiry question at the top of every single handout and connect to it every single day.

2. Center on a narrowed inquiry question

You will know when you have a strong unit inquiry question and subtopics, because these narrowed questions will write themselves.

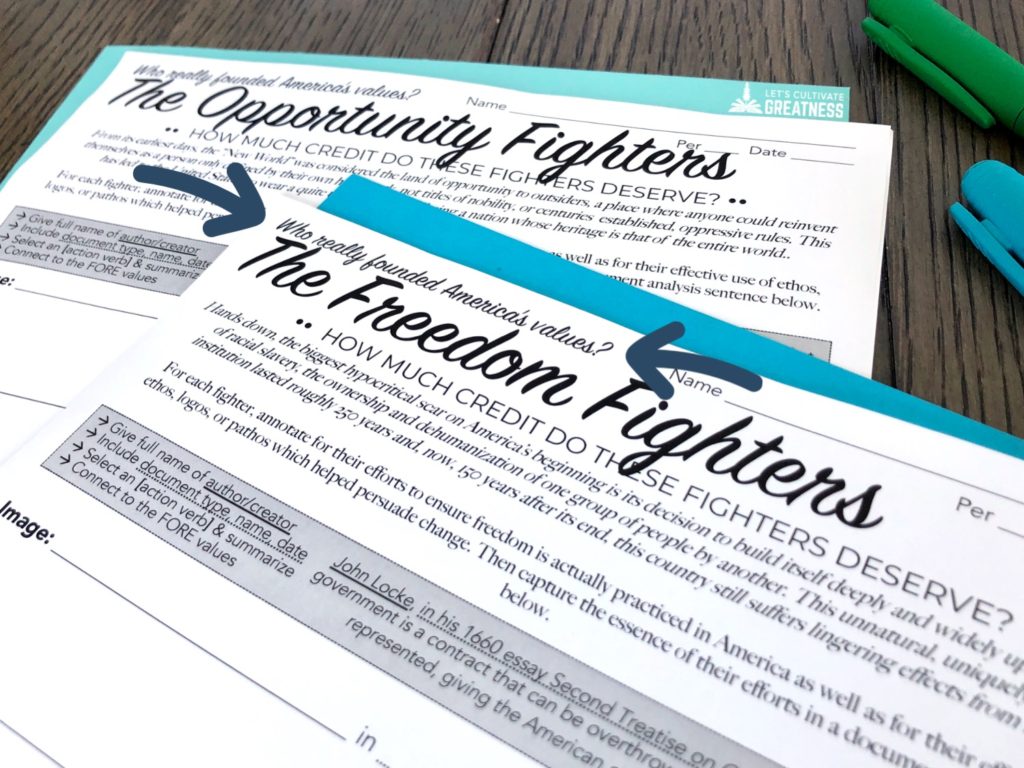

In the case of my Founding Values unit, remember the overall inquiry is “Who really founded America’s values?” So, the subtopic questions are “How much credit do freedom fighters deserve?” and “How much credit do opportunity fighters deserve?” and so forth. In these two cases, the activities focus on the abolitionist and labor movements.

In my Hero unit, I ask, “What makes an American hero?” and we focus on various twentieth century American experiences that could arguably be heroic. In that unit, the subtopic question template becomes “Is this experience heroic?”

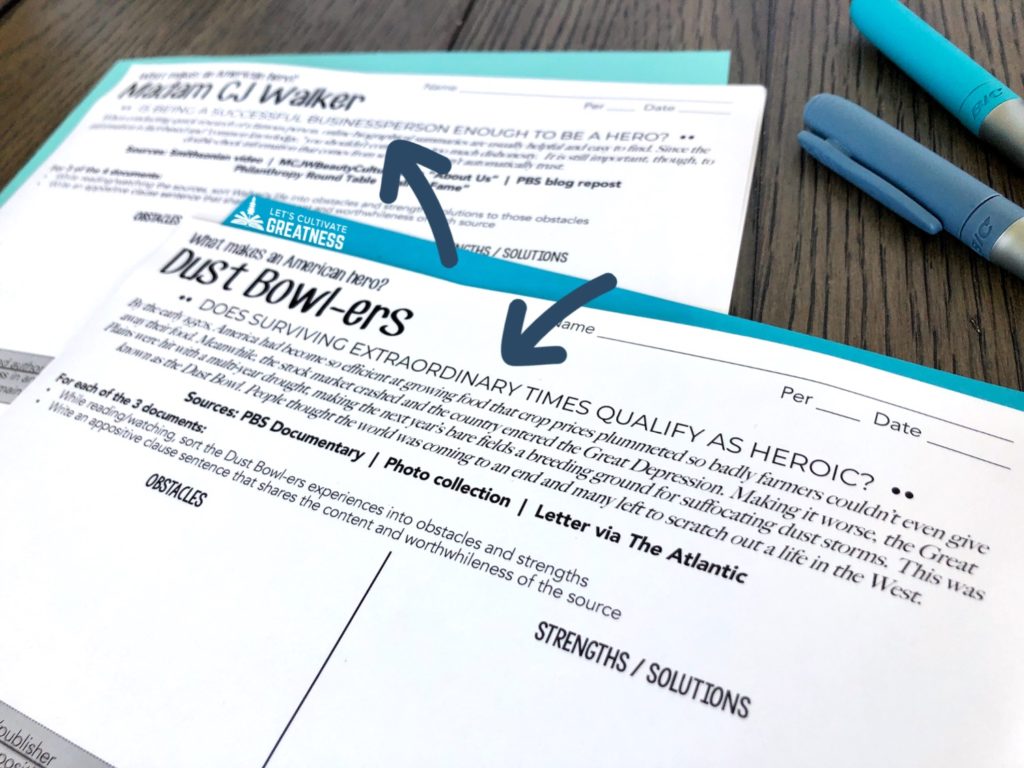

I’ll give you a few examples. We start with Madam CJ Walker, whom I selected for obvious reasons: her experiences as a Black woman in Jim Crow America, her business savvy and success, and her later philanthropy work. For her, the narrowed question becomes “Is being a successful businessperson enough to be a hero?” This challenges students to grapple with whether self-made wealth on its own is heroic, or if there is an expectation to return some of that fortune to society.

When we move onto a less obvious topic, the Dust Bowl, the question becomes “Does surviving extraordinary times qualify as heroic?” as we study this seemingly apocalyptic experience and how people adapted.

Your actual activities can be any number of things: completing primary source stations, watching a documentary, or examining web-based material, for example. If you have been teaching for a few years, you have your favorites, I’m sure. If you need some help brainstorming, feel free to email me.

Throughout your subtopic activities, connect back to that narrowed question. Put it on your whiteboard, your slides, your handouts and talk about it constantly. Just like the unit inquiry question.

Action item: Put the subtopic question on every related handout and connect to it each class period, just like the unit inquiry question.

3. Give focused background information

One of the biggest mental hurdles of switching to teaching thematically is figuring out how to present the overview information, which is usually done with lecture and textbook reading.

I don’t do either, at least formally. Instead, I give just what students need to know in order to grapple with the question at hand. I talk briefly with some slides for 15 minutes and may give students a curated tertiary source, but I keep them short in my on-level courses. Honors or college-credit courses will look differently in this regard.

With teaching thematic history, you let go of the idea of trying to cover everything. Not only because inch-deep-mile-wide is boring, but also because it doesn’t stick. The fantastic book Made to Stick details this brain science.

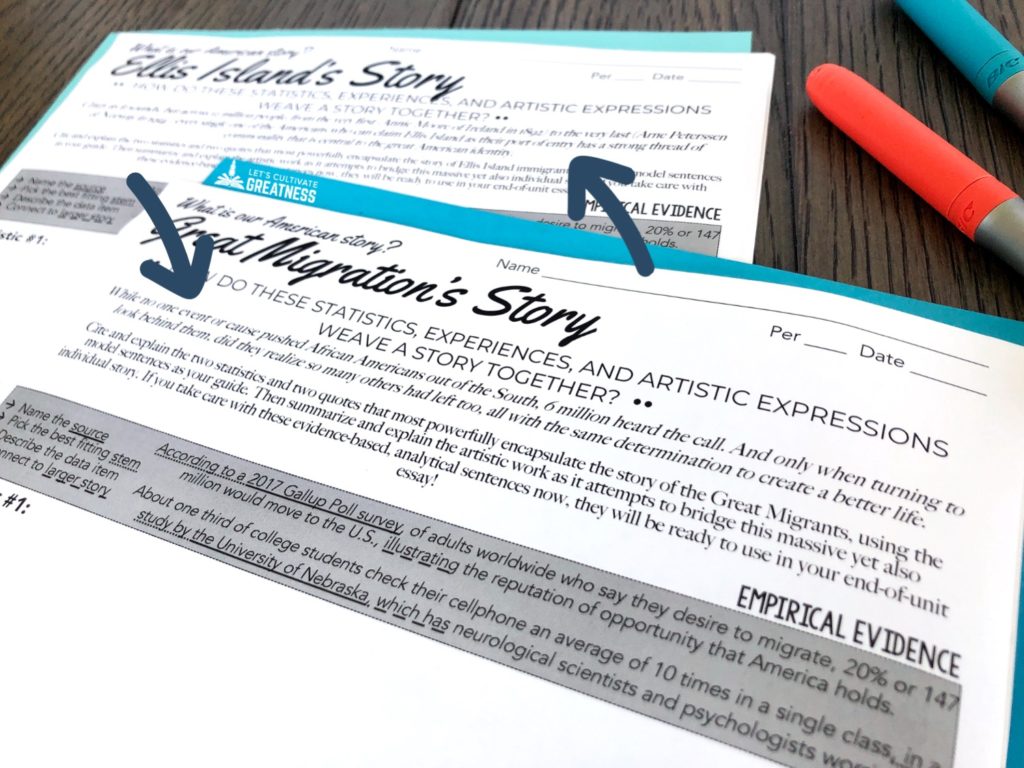

For example, in my Immigration unit, the lessons center on exploring personal accounts of immigrants, so I supplement with statistical data and visual sources of those groups.

As I introduce our Ellis Island subtopic, I display a handful of powerful photos as I talk about the “new” immigrants. Then students annotate a one-page overview full of statistics. That’s it. Because the real learning happens when they analyze various interview transcripts after this introduction.

I do the same with the next subtopic on the Great Migration, before student-read excerpts from The Warmth of Other Suns and then again with our Vietnamese refugee subtopic before watching the documentary Nailed It.

Never does it feel like a lecture for students nor me, rather it’s compelling storytelling and foreshadowing.

I also write a 2-3 sentence contextual statement on the activity handout, at the top under the narrowed question. This reinforces this overview and fills in the gap if a student missed that day.

Action item: Add a brief contextual statement to your handouts that cuts straight to the importance of the content about to be learned.

4. Challenge students to take a position

Close each subtopic with a direct tie-back to the overarching inquiry by having students take a position on the content. This is easily accomplished with a few sentence stems.

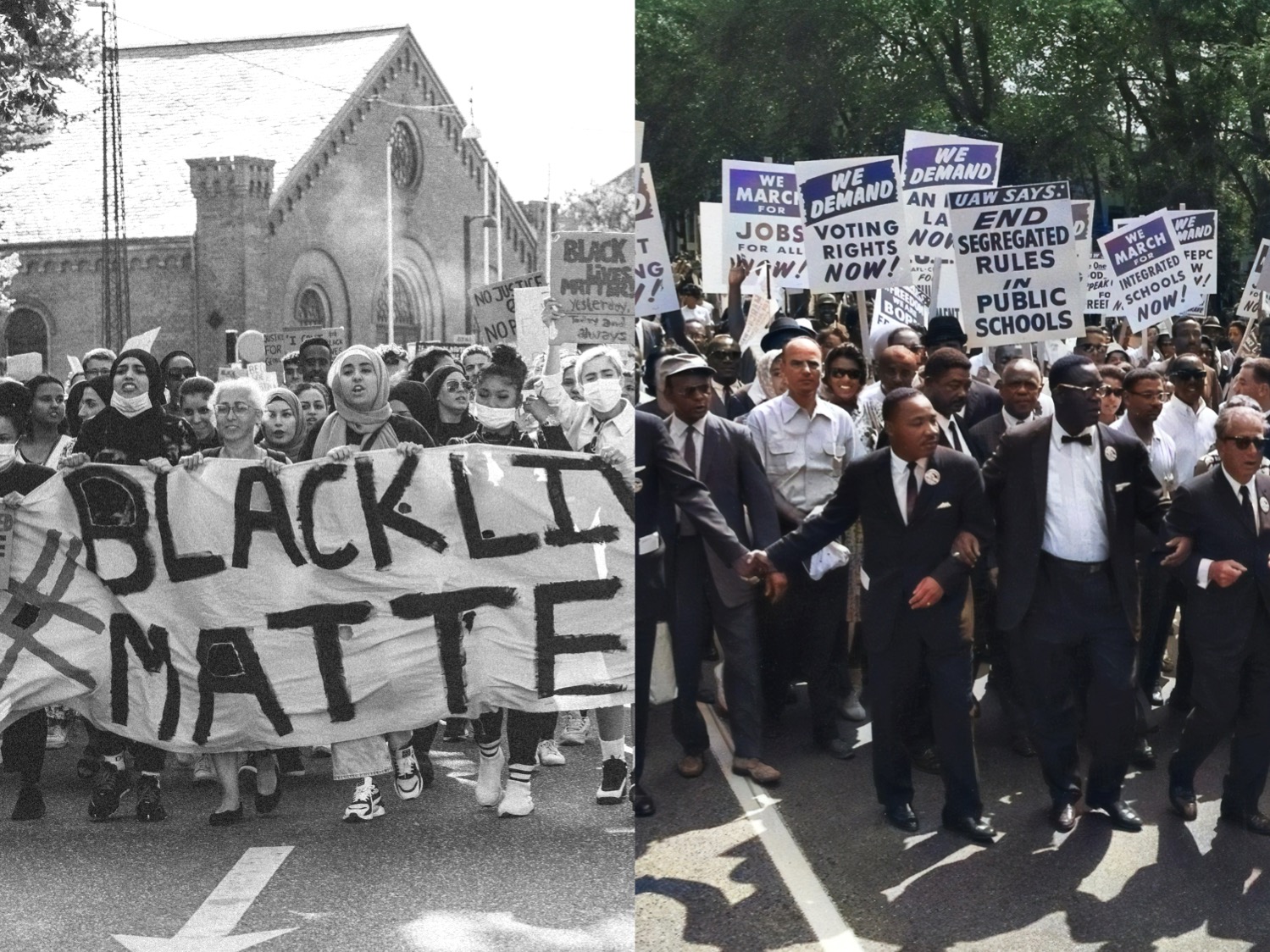

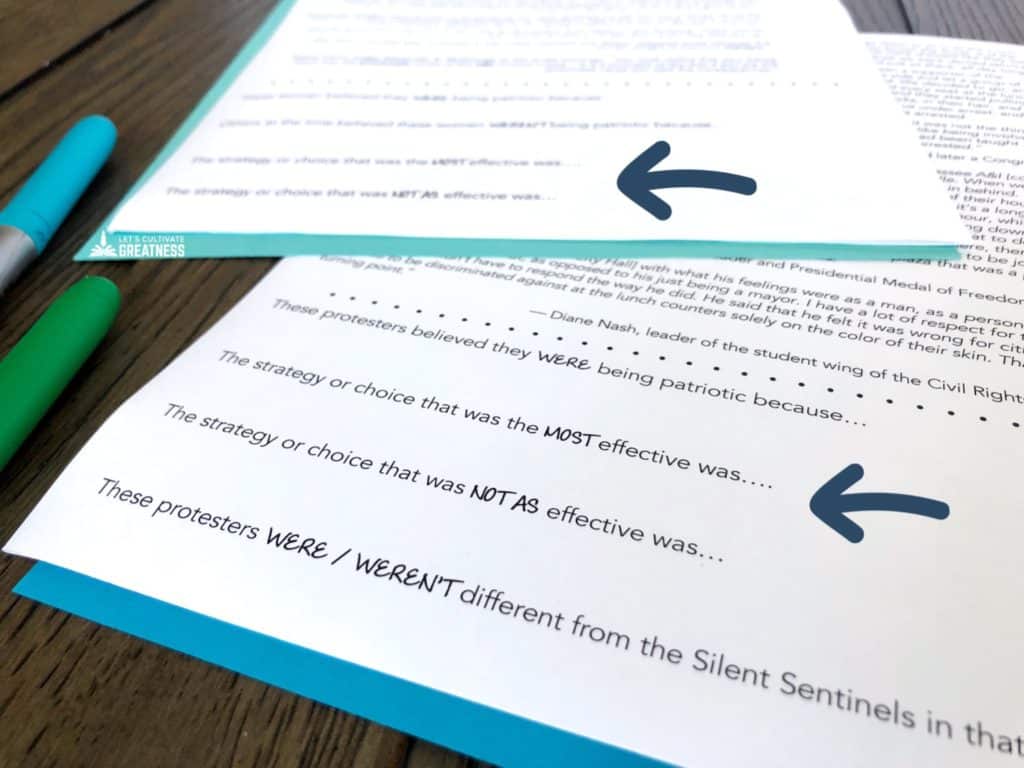

For example, in my Protest unit we explore the big question of “How patriotic is protest?” by examining a handful of 1900s protest movements. Each one represents different social movements and different protest strategies. This means students are set narrowed questions like, “How patriotic were the Silent Sentinels?” and “How patriotic were the sit-inners?”

To conclude each movement, students finish sentence stems like “These protesters felt they were patriotic because…” and “The most / least patriotic aspect of their protest was…” These stems are meant to be short and direct, yet open-ended enough for students to develop and own their supported position as they grapple with the role of protest in American history.

These firm statements also (unbeknownst to the students!) become topic sentence rough drafts for students’ end-of-unit DBQ essays in which they answer the unit inquiry question. Because why are you asking such a question, if students don’t ever actually answer it? Click here to read more about how to build a DBQ-centered classroom.

Action item: Use sentence stems at the end of each subtopic to force students to declare a position on the narrowed question.

5. Evolve the inquiry question’s central concept

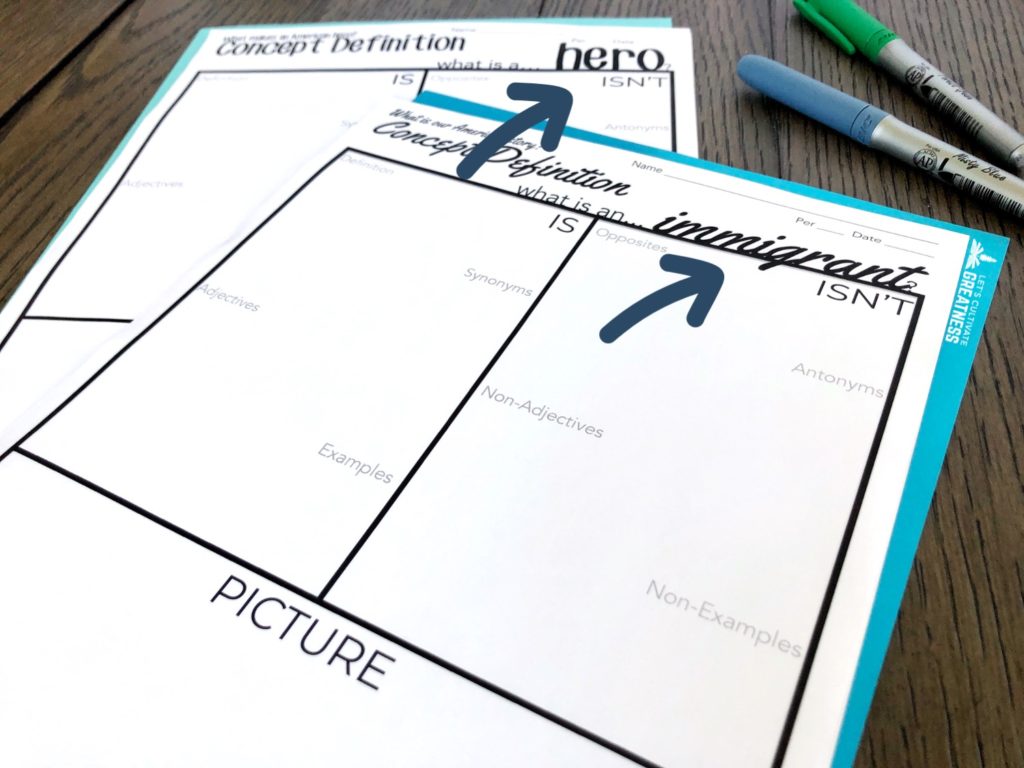

A good inquiry question is centered around one main concept. You’ll notice my US History units center on things like immigrant, protest, and hero. One purpose of a thematic unit is to have students develop a far deeper understanding of a concept, one that they’ve made relevant to their lives.

After each subtopic, students add new and deeper meaning to an on-going concept notes sheet. I use a graphic organizer based loosely on the Frayer Model. Students add a few words each time and by the end of the unit they have developed wisdom about the concept, not just understanding.

I use these concept definition graphic organizers across all my classes (even Leadership!) because this exercise in deep thinking is so impactful. Plus, their thoughts will astound you.

Action item: Have students add to a growing definition of the unit’s central concept.

If you need help getting started, be sure to read my blog post on designing your first thematic history unit first! I can’t overestimate the way a thematic approach has upgraded my impact as a history teacher and I love to pass along my discoveries you.

Feature image credits: Jeppe Monster and History in HD