One of my favorite parts about teaching social studies is that there is inherently never a right answer.

For being a huge rule-follower in every other aspect of my life, when it comes to learning, I’ve always been more fascinated by thinking about what all the possible answers are, rather than what is the one right answer.

Studying history is all about learning the endless shades of gray. Which means my favorite question isn’t “Why?”, but rather “How much so?”

Why is still in the “who, what, when” boat in that it implies a right answer exists—that history and people are a done deal. Or that if there are multiple answers to why something happened the way it did, those answers are in separate camps rather than overlapping and blended.

This three-word question is one of those teacher hacks I discovered from just trying it one day and instantly seeing how well it worked. In the space of just a few seconds of precious class time, it up-levels student thinking by forcing them to qualify, with an amount word, their position.

Students say comprehension-level, even common sense, statements all the time: “Slavery is bad,” or “Johnson’s Great Society tried to end poverty.” When that happens, all you have to do is ask “how much so?” and they are forced to pause and think of the spectrum of evidence they know in order to own a firm position with a precise word.

What’s more is that “how much so?” places ideas, actions, and choices along a continuum, rather than a yes/no, good/bad dichotomy. It helps show students that others can have positions all along the line, so there is no single right answer.

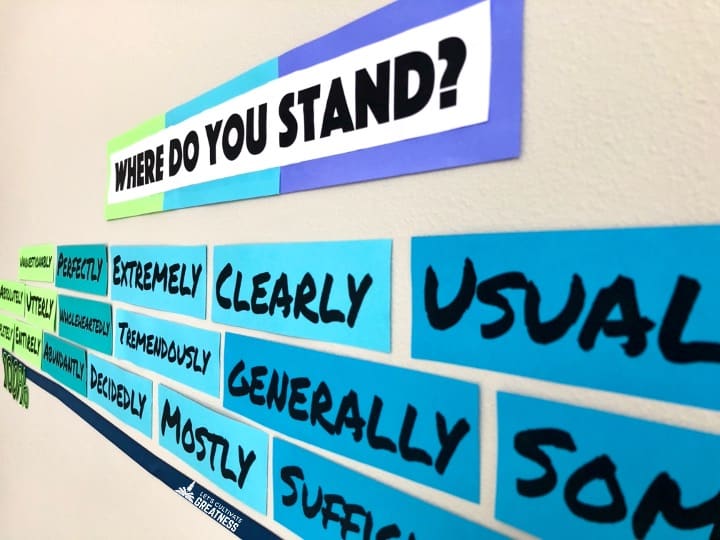

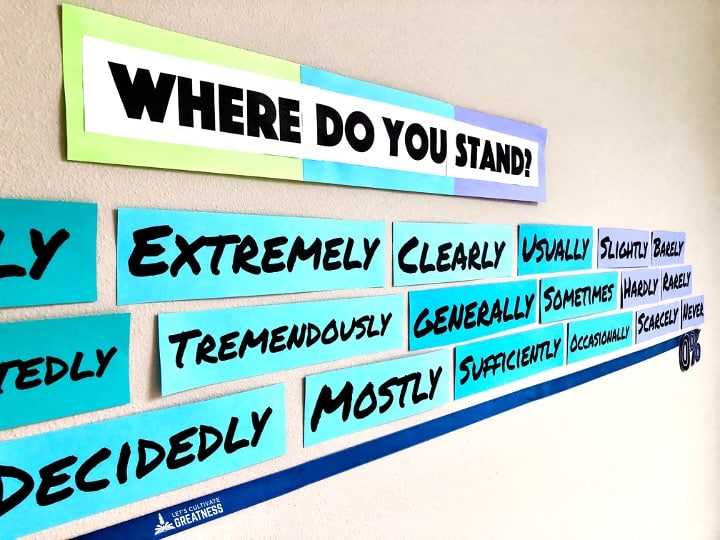

After realizing how effective this question was and how frequently it can be asked, I developed an argument qualifier line to support students in this skill.

What is an argument qualifier line?

If you want to get nerdy, an argument qualifier is one of the six components that philosopher Stephen E. Toulmin identified in his method of argumentation. It’s the acknowledgment that a claim is never always true. And this is a big “ah-ha” that most high school students haven’t made yet when it comes to thinking about history—that history is more claim than fact.

Simply put, it’s a continuum line of amount-type words from never to entirely. In practice, this line often stays intangible, and we expect our students to simply draw on it from their mental database. Nope. If you want students to use academic words and skills, you’ve got to give them the tools. So, let’s make it a literal line.

Creating an argument qualifier line

First, gather your words. It’s kind of fun searching for all those words students know, but rarely use in their everyday vocabulary. Like staggeringlyor scarcely. You can get as extravagant with your thesaurus as you’d like, and, honestly, students have fun picking the more interesting words, but here a list of basics to get your continuum line going.

Never

Rarely

Scarcely

Slightly

Occasionally

Partially

Often

Sufficiently

Mostly

Usually

Decidedly

Extremely

Tremendously

Overwhelmingly

Completely

Staggeringly

Absolutely

Unquestionably

Entirely

Once you have a few dozen words, print them in a large, easy-to-read font and grab a roll of wide ribbon or tape. Then, decide where the words go along the line. Is staggeringly more than unquestionably? What a great question to ask your students.

On the line I also like to put a few percent markers—100%, 75%, 50%, 25%—to give students a bit of a familiar foundation.

You’ll want to find a place in your classroom to display your line that can be easily seen by every student. I have mine under the whiteboard. If that space is already filled, don’t be afraid to create a vertical line in a narrow spot or, if short on wall space, get creative and make your line stretch across several cabinet doors or the front of your desk.

I recommend creating a handout version as well for students to keep close.

Incorporating argument qualifiers into your lessons

Once you start thinking in terms of “how much so?”, you’ll see opportunities pop up all the time to ask it in class. But still, I know it’s helpful to see some examples of when you can deliberately use this tool, so here are a few ways I intentionally build lessons that use the continuum line.

When analyzing primary sources.

After reading a source or examining an image, ask students, “How angry does he sound?” or “How nerve-wracking must that have been?” or “How clever was her argument?”

When reviewing at the end of the unit.

Put down a long strip of tape or string on the floor (or out on the sidewalk, if the weather’s nice) for students to stand along. As you pose all sorts of questions covering content learned, have students declare their literal position with their feet. Ask them to announce their word and provide evidence to support it.

For example, if you are reviewing a WWII unit, a few questions you could ask are “How worried do you think Albert Einstein was to send that letter to President Roosevelt?” or “How effective were the victory garden efforts?” or “How long-lasting were the gains made by women in the workforce after the war ended?”

You can even have students develop and ask their own questions.

When assigning formal essays.

This may be the one that teachers think of the most readily when looking at this tool. Whether for a collaborative DBQ essay, an in-depth capstone research project, or an on-demand timed essay, this tool is crucial.

During the outlining stage, have students declare their word. I go as far as having them write it right on the top of their outline sheets to focus and commit them. It also gives me an at-a-glance assessment of their thinking as I walk around.

Supporting historical thinking skills with argument qualifiers

Every historical thinking skill involves the need for qualifiers, yet we may not be extending past the how by routinely asking students how much. I can’t stress enough how much that little addition hones the thinking students have to do. Thinking that’s not terribly more difficult, but that won’t happen unless they’re prompted.

This doesn’t mean every single essay question or unit inquiry needs to start literally with “How much…,” but in some way an amount is inherent and necessary for students to declare, whether it is in day-to-day discussion, in analyzing sources, or connecting events from throughout the unit. Here are a few question templates to show how argument qualifiers exist in each historical thinking skill.

Change and Continuity Over Time: How much did X change? How much did Y continue?

Cause and Effect: How much did X cause Y? How big were the effects of X on Y?

Compare and Contrast: How much was X similar to Y? How different is X from Y?

Periodization or Contextualization: How much did X represent the era of Y? How much did X influence Y?

Ethics: How justified was X in doing Y? How much credit does X deserve for Y?

I hope this tutorial has changed the way you think about teaching historical argumentation. To make it easy, I have put together my Argument Qualifier Continuum Line in an easy print-and-go downloadable kit, including an editable version so you can customize it for your classroom and start up-leveling your students’ argument skills.

Feature image credit: Katerina Holmes