Primary source analysis is the cornerstone to teaching history these days. And once you have a few good analysis strategies in place, it’s easy to assume your students can seamlessly turn their thinking into equally great writing.

Unfortunately, if you jump into assigning a DBQ essay too quickly, you’ll immediately realize it when you are met with a stack of disorganized, vaguely worded essays to grade.

It’s a mistake all history teachers find themselves in—believing our students’ high-level thinking will transition right into high-level writing.

I am totally guilty of this. It took me multiple times of losing students across that leap to realize I was missing an important step.

We know students need step-by-step support to deeply analyze primary sources, but they also need that same level of guidance to create concise, cohesive, and original writing. We need to devote careful instruction to both.

But before we dive in, if you feel your source analysis lessons still need some help, check out my favorite primary source analysis strategies kit, which you can download for free! Then head back here.

Now that you’ve got that taken care of, I want to share my favorite 5-part strategy for that in-between practice of source analysis and full-blown-DBQ-essay-writing.

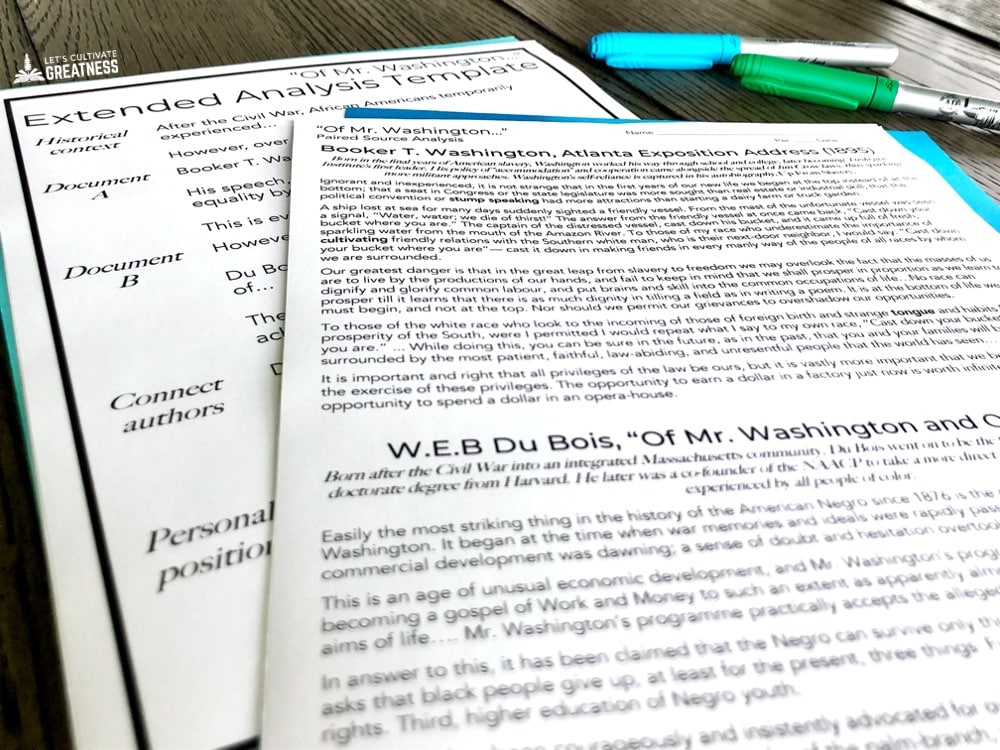

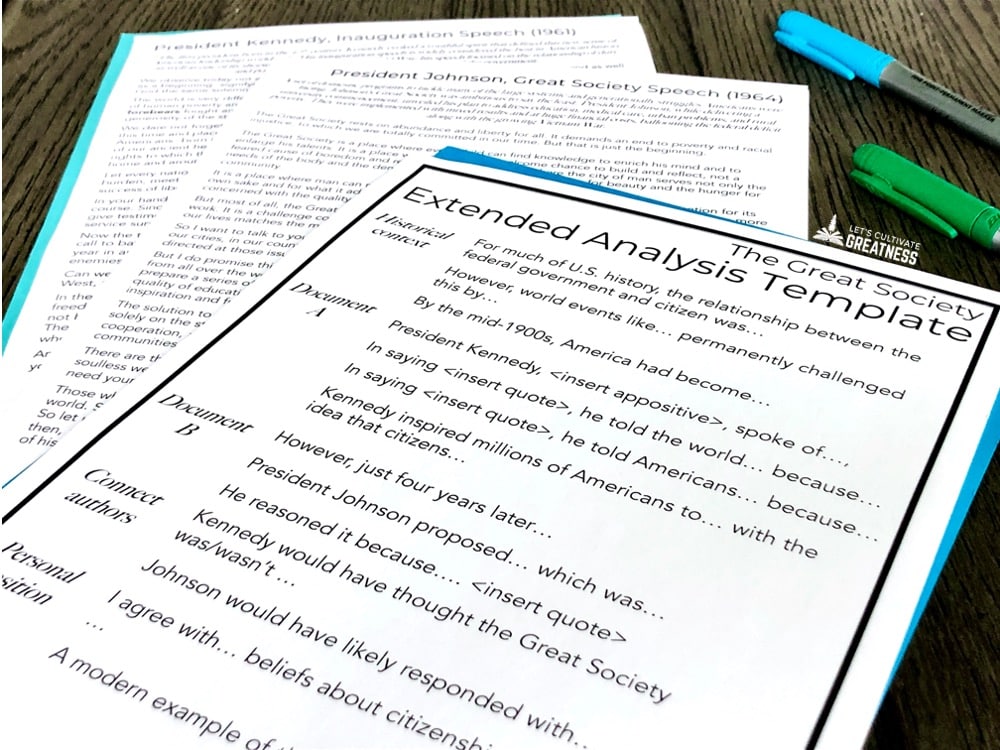

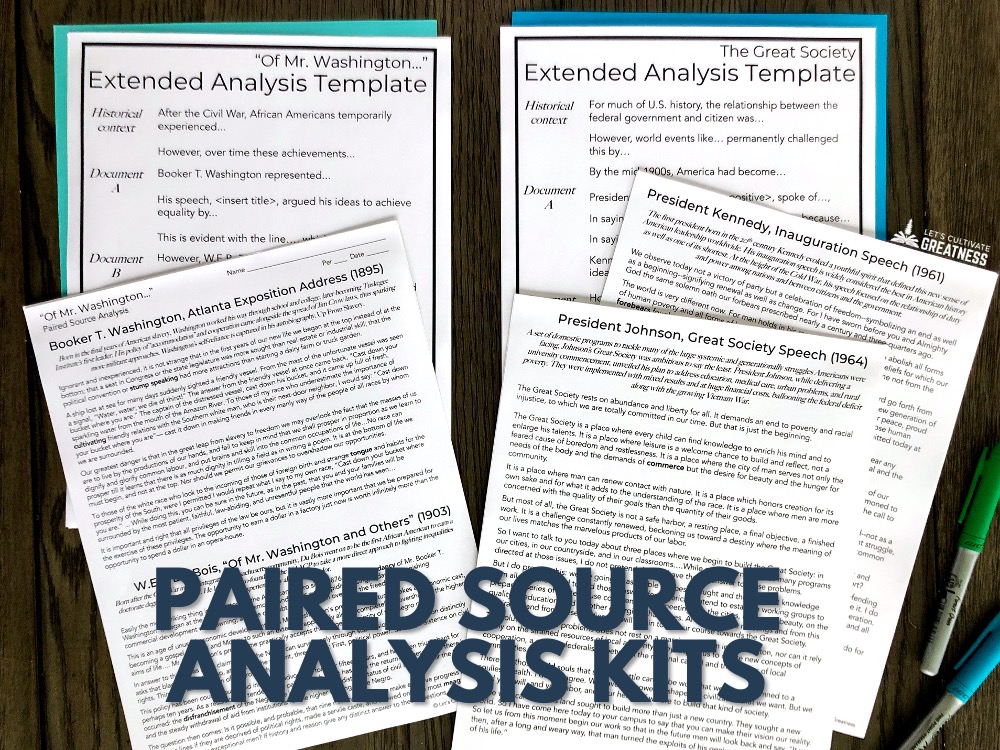

I call it Paired Source Analysis Writing and because it focuses on just two complementary sources, it is a great stepping stone to more formal DBQ essays. Also, by focusing on two distinct ideas, students can more easily form their own position and practice proclaiming it in their writing.

And that’s the whole point of learning: for students to grapple with new knowledge, arrange it among the ideas they already have, and conclude with an evolved personalize understanding as a result. So, let’s get started!

1. Pick Two Opposing Sources

These don’t have to be ones in extreme opposition, like a Federalist and Antifederalist essay or Booker T. Washington and WEB Du Bois’ ideas on post-Reconstruction equality, though those pairings are obvious choices for this exercise.

It could be two speeches given by the same person that show change over time, like President Lincoln’s first and second inauguration addresses or President Hoover’s inauguration speech in early 1929 and a campaign speech from 1932, which in both cases were delivered to the nation against two very different backdrops.

It could even be two texts where one caused the other to be created, as was the case with President Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms speech inspiring Norman Rockwell’s iconic Four Freedoms paintings.

The key thing to remember is that there is room for your students to insert their own opinion as a result of seeing two others.

In this paired source exercise, I recommend keeping the excerpts to less than a page each. I strive for about half a page. A little longer than typical DBQ essay excerpts, but still not overwhelming.

2. Prime Students’ Thinking

Prior to introducing the sources, ask students their opinions on related ideas. I often do a Four Corners exercise to get them up and moving to kinesthetically feel their positions. This helps all students, but particularly lower-level students, in combating the abstractness inherent to historical thinking. After reading, we always are gesturing back to the physical corners of the room in discussing the sources.

For example, when we cover the Great Depression, I have students grapple with questions about the role of the government towards the citizen in the midst of recessions and, likewise, what the citizen owes their country during this time. I ask questions like:

Does the government have a responsibility towards the unemployed? Should it be greater during a recession?

Do citizens have a responsibility towards the government? Does it change during a recession?

Do citizens have a greater responsibility towards each other during a recession?

Around the room, signs are posted that say “Absolutely yes,” “Yes, but…,” “No, but…,” and “Absolutely no.” Students pick one to stand at, then share out and discuss their thinking.

They are now perfectly primed to examine the song lyrics to “God Bless America,” which enjoyed a resurgence in the 1930s, and Woody Guthrie’s more cynical response, “This Land is Your Land.” This is one of my favorite paired source analytical writings we do all year.

3. Preview Sources with Clear Annotating Tasks

Give some backstory and context for the two authors. This lets your students make great connections between someone’s perspective on the world, their audience, and their purpose in creating their work—the trifecta of sourcing.

For example, in pairing an excerpt from Andrew Carnegie’s well-remembered “Gospel of Wealth” essay with the wildly-popular-at-the-time “Acres of Diamonds” speech by Russell Conwell, I preface with Carnegie’s humble origins as a poor immigrant, his self-made millions, and his audience of fellow millionaires. We brainstorm what possible message he felt compelled to share with his peers. Inevitably, this leads to a student bringing up Bill Gates and his philanthropy mission.

Our annotating task then becomes marking for how Carnegie regarded wealth—what the wealthy should do with their money.

In contrast, Conwell was a man delivering his speech over and over to middle and working-class people, so I ask what message he was likely sharing. Easily, students guess it’s an inspirational “you can be wealthy, too” speech so we know to mark for his message of wealth’s attainability by anyone who wants it enough—a prevailing idea at the time.

This prefacing with a clear purpose for reading creates accessibility for all levels of readers, and it will help students write with specificity as well.

4. Develop Students’ Opinion

After reading the two sources, give students time to connect the authors’ ideas to what they themselves discussed prior to reading. Remember, my gesturing back to the corners of my classroom? This is where students form their more developed positions. Some general questions you can ask at this step are:

How did these sources change your position on this issue? What about on your understanding of this era?

Whose position do you most agree with? What is something on which you can agree with the other author?

Whose position was likely more popular at the time? What about in today’s society?

If a third source was added to best complement these two, what position should it take?

5. Provide a Scaffolded Template

This is the most important step and the one that so often gets leaped over. You need to provide sentence starters and step-by-step guidance here to strengthen your students’ skills, which are needed for the more difficult DBQ essay.

We follow a predictable 5-part formula when writing ours:

Part 1: an introductory sentence to lay the historical context

Parts 2 and 3: A couple sentences each discussing each author, the source, and supported by a quote

Part 4: A sentence or two connecting the two authors and their ideas

Part 5: A conclusion sentence in which students are able to insert their own idea on the topic and/or connect the issue to modern time.

If I am deliberately building towards explicit DBQ writing, we will also include a sentence that incorporates a related outside piece of evidence.

When we write these extended paragraphs, I really do mean step-by-step. I post the sentence stems one-by-one. No matter what time of year, this slowed-down, fine-tuned approach is worthwhile for all students.

Don’t think that just because you have done this exercise before, you can rush through it the second time or that your college-bound students don’t need this slowed approach too! You’ll be amazed what your students will be able to master with source-based writing in your history classroom with just a little scaffolding and support like this lesson format.

If you are ready to up the source-based writing in your history class, this collection of Paired Source Analysis Kits is ready to go for you. These are great to complete once per unit or so to regularly practice higher-level writing in a low-stress setting.

Feature image credit: Debby Hudson