Your Civil Liberties or Judicial Branch unit isn’t complete without spending a few days teaching about landmark Supreme Court cases.

However, many cases have this distinction, so deciding which ones to include can be hard. Below, I share how I select the cases we cover in my high school Civics and Government class and the poster project gallery walk we do to learn them in a way that matters.

I like including several cases to help students see the nuances of the judicial process. That way, students aren’t just memorizing a bunch of case names and matching them with one-sentence summaries but understanding exactly how their taken-for-granted Constitutional rights came to be over time.

If I can get them to appreciate the careful weighing and fine-tuning involved (and just how recent some of their rights are!), I feel I’ve done my job.

What is a “Landmark” Supreme Court Case?

Unlike the seven or eight Constitutional principles or the 27 expressed powers of Congress, there’s no definitive list of landmark Supreme Court cases or clear-cut criteria for what gets this distinction.

Generally, a Supreme Court case is considered a “landmark” if it significantly changes the interpretation of a law, setting a new precedent for future cases.

However, clearly defining the boundaries of what something like a Constitutional right is takes several court decisions. So by default, there have to be many.

And now, with over 200 years of precedents set, you’d think there wouldn’t be any legal areas left for the Supreme Court to make anything more than minor refinements.

But as Supreme Court Justices come and go, as new technology always raises new tricky questions, and as social norms are ever-shifting, there will always be landmark decisions being made.

I always make sure to include recent cases to help illustrate this point.

How to Decide Which Landmark Cases to Teach?

First, consult your state standards. Usually, there are at least a handful of specific cases mentioned. The most I’ve seen, though, is only about a dozen of the most well-known ones.

Don’t take that to mean you should stop there. I’ll explain why in a second.

Then, see what various credible government and non-profit civics websites have listed as landmark cases. These will be longer lists, but still only a couple dozen. You’ll notice some cases appear on every list, but many are different.

Add all of them to your growing list. And start sorting the cases into categories, like free press or capital punishment.

Because here’s the harm in all these short lists of 10-20 cases—they lose the meaning of what the Supreme Court does, which is to refine the precedent set (very rarely overturning themselves).

If you just teach Brown v. Board, you’re continuing the overly simplified impression that one case ended segregation. Even if you include Plessy v. Ferguson, it still conveys the work of the Court on a this/that binary.

The lesser-known cases of Sweatt v. Painter and Plyler v. Doe tell the more complete story of the equal protection clause and education.

Or Griswold v. Connecticut paving the way for Roe v. Wade (and now, Dobbs v. Jackson that overturned Roe).

I recommend a handful of cases for every category you pick to create a bit of a timeline of evolving rights. Also, if possible, include cases that expand and limit rights.

Wikipedia has an extensive list of landmark cases pre-sorted by type. I don’t recommend starting here because it’s probably too many cases to sift through.

But because you’re now familiar with several more prominent ones, you can skim through this long list and better decide which cases to select.

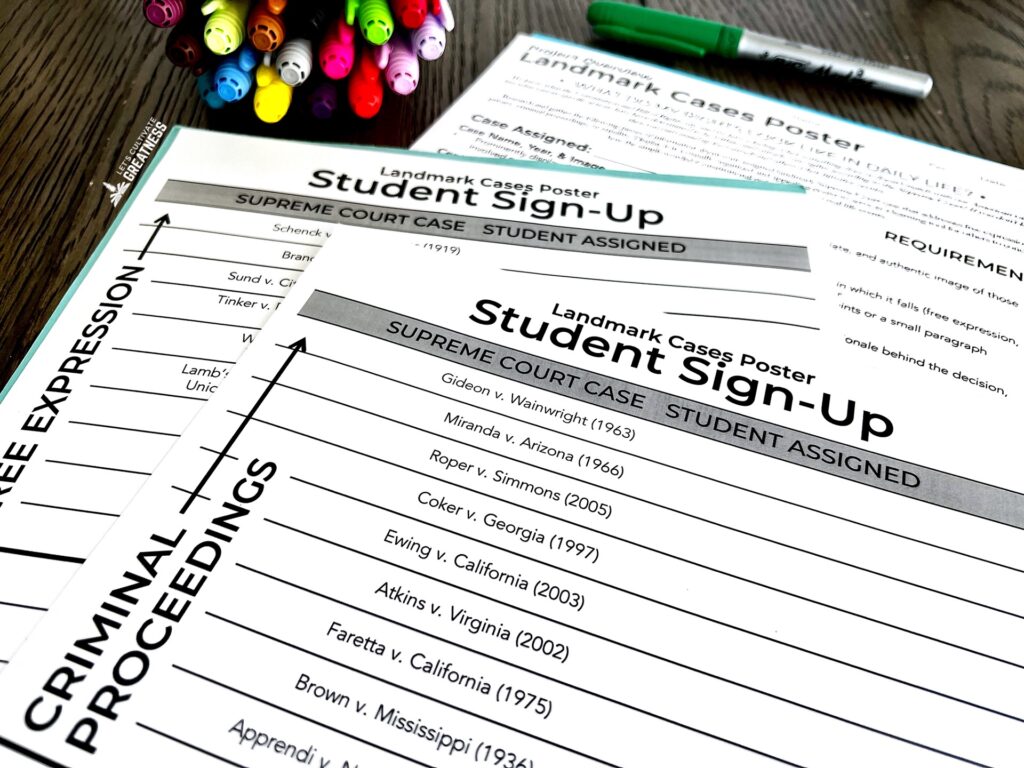

I focus on four broad categories for this project—free expression, privacy, criminal proceedings, and equal protection—and have 10-12 cases for each. Choose whichever categories make sense for you!

Select roughly as many cases as you have students, so each has their own case.

For those important cases that are more stand-alone, I weave them in other places in my Civics class. For example, United States v. Nixon is commonly listed, but I cover it in my executive branch unit.

Before Teaching these Cases

Analyzing landmark cases is really the culmination of your Civil Liberties or Judicial Branch unit, so I recommend placing this at the end.

First, students need a solid overview of how the federal court system functions. This can be done with a lecture, textbook reading, or even a few podcasts or videos.

If you are super short on time, this 5-minute Vox explainer video on the Supreme Court does a good job covering the basics.

For the class or two before, we do this fun simulation activity where students experience interpreting laws in various scenarios, feeling what it’s like to be a judge.

Lastly, you’ll also want to have students familiar with the Constitutional excerpts related to the cases you select.

Now, your students are ready to learn and teach each other about these cases!

Landmark Supreme Court Poster Project

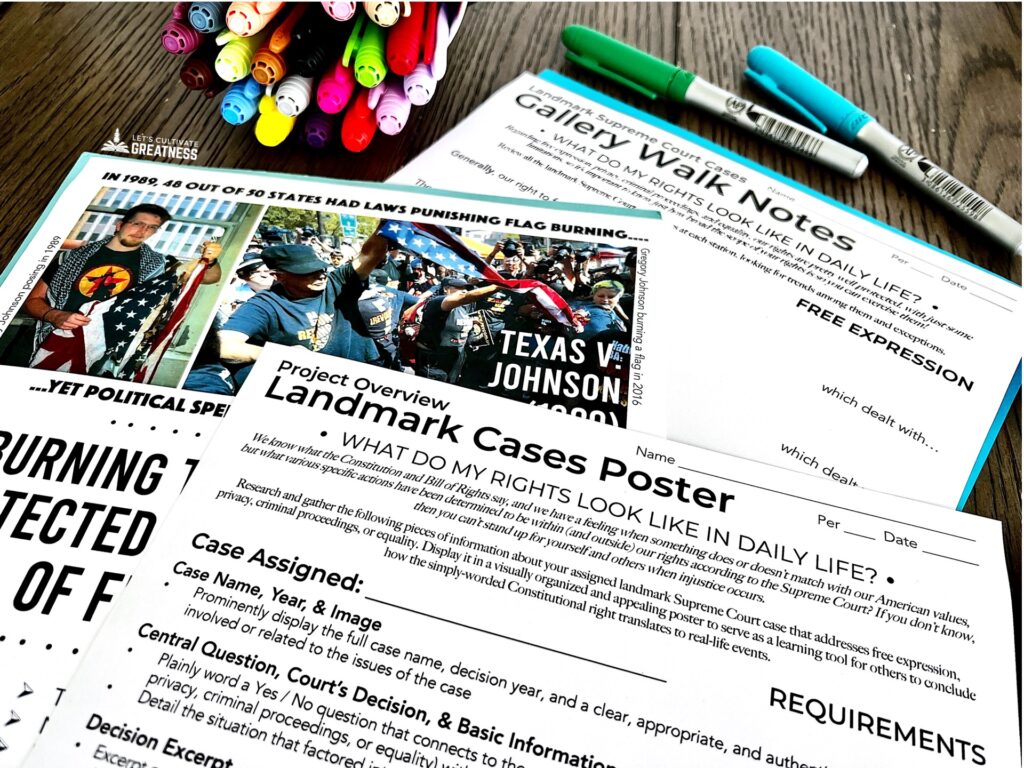

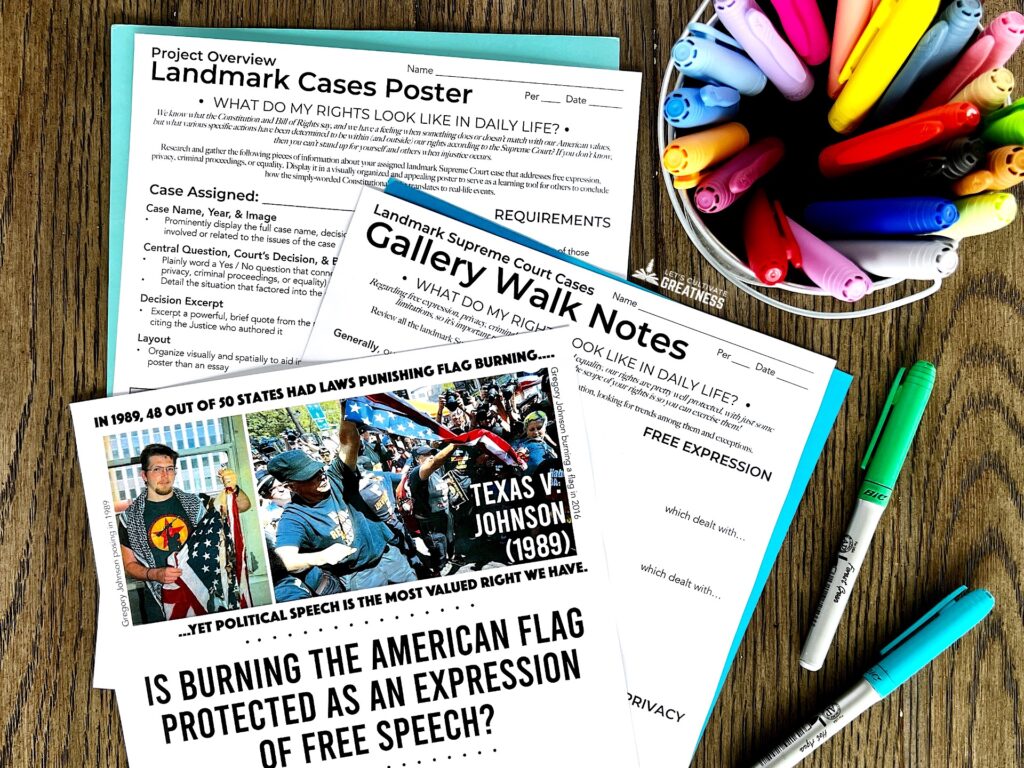

Select one case to use as a model. Give a short overview of its background, outcome, and lasting impact. I like to use Texas v. Johnson because it’s a straightforward case that also illustrates the struggle of applying the law.

I then show them the sample poster of the case to use as their model.

Assign students their cases and have them create one-pagers or posters briefly capturing the issue behind the case, the rights involved, what the Court decided, and a key expert from the majority opinion.

Students aren’t doing extensive research, so sources like Oyez’s case summaries are perfect.

Create a gallery walk with their posters. I display the cases within a category together to reinforce that secondary element that the Court refines what rights mean over time.

This way, students make connections and conclusions about the whole of a particular right—like what exactly is and isn’t Constitutionally protected speech—rather than rote copying information down for each individual case.

Your students should walk away with a solid grasp of significant cases that have shaped our Constitutional rights. But even more importantly, they’ll understand how this is a fluid process, which is why their voice and vote matter.

You can get this complete project with pre-selected cases organized into categories in my store.

Grab my Landmark Supreme Court Case Poster project kit for a done-for-you 2-3 day lesson, perfect for your high school Civics and Government class. Or check out my Civil Liberties or Judicial Branch units, which also include this project.

Feature image photo credit: Jackie Hope