We call it Civics, not Government, class because the purpose is to instill a sense of citizen duty and participation, not just a memorization of names, flow charts, and Constitutional provisions. Yet, in reality how much of our class time is dedicated to empowering experiences to fulfill this former ideal?

Probably less than we’d care to admit, right?

I recently visited beautiful Charleston, South Carolina to explore its history as one of America’s original metropolises, tragically built and originally maintained by the enslaved labor of thousands of human beings.

Of course, this trip meant a ferry boat ride out to Fort Sumter in the middle of Charleston Harbor. A history teacher friend told me to make sure I was on the first boat ride out in the morning in order to participate in the day’s raising of the flag ceremony.

My friend was right. It was a powerful experience in the meaning of American civics and history.

Each day, National Park Service officials invite their guests—specifically calling out for veterans, children, immigrants, people of color, women, all Americans—to assist in the raising of the national flag (and in the evening, to lower it). They are simultaneously honoring the perseverance of the ideals of American democracy in this daily task, while also transforming the nation’s most divisive and exclusionary moment into a diverse and inclusive one.

I was humbled and grateful to help lift up the flag that morning, knowing it represented endurance, but also evolution. That is civics. Participating in molding one’s society and government. Knowing the past in order to engage in the present.

But so often in the classroom it just comes down to time. The time to dream how to build a course that empowers students. The time to plan these great ideas. And the precious class time to implement them.

One thing I’ve learned over the years, though, is that powerful civics projects don’t have to be extensive. There are many acts of civics that are super quick and even quite informal.

If you are looking to weave in more actual civic participation into your middle or high school Civics course, here are 5 easy-to-implement ideas.

(Pre-)Register Students to Vote

If your students are of the proper age in your state, schedule 20 minutes to register or pre-register them to vote. Many states allow citizens to register online, others use a downloadable single national form, and some allow 16- and 17-year-olds to pre-register early using driver license records.

Procedures and deadlines differ by state, so be sure to look into this well before Election Day. A great day to set aside class time for this is on the fourth Tuesday in September, which has been designated as National Voter Registration Day.

To learn how to register in your state, Vote.gov provides a great starting point.

If your students aren’t old enough to register, use this time instead to model how it’s done and how to confirm one’s registration is up to date.

Remember to stress to students that Americans also have the right to not register to vote, so no student should feel pressured to register if they don’t want to.

Email or Call Government Officials

Find ways to connect with officials throughout your course. These are just two of the ways we do in mine:

In an odd-year election in which local races are usually held, I have students write candidates questions as part of their research. We type all our questions into a single file, then wordsmith them collectively, before I send them off with a bit of an explanation.

You better believe my students judge and decide which candidates they support from the answers they receive. We only do this with mayoral and school board races, in order to better ensure we get responses. Still, I get chills watching how invested students get, especially knowing these races are the ones that perennially suffer from lower turnout.

Also, a couple of times in the course, have planned moments when a wondering is raised that’s truly only best answered by an official’s office, not Google. That is when I challenge my students to volunteer to call and ask it, right there in the middle of class. Trust me, your wide-eyed students won’t think you’re serious, but let them know you entirely mean it.

In my three branches unit, we look at the practice of Congressional town hall meetings and how so few are held. Towards the end of the lesson, I intentionally guide them to arrive at the question, “How many town hall meetings have our own elected members of Congress held this year?”

So, smack in the middle of class, I ask if three students are willing to call our U.S. Representative and two Senators and ask.

I provide them with this basic script:

“Hi, my name is… and I am a student at… which is located in… A question came up in my Civics class about Representative/Senator So-n-So and I am wondering if I can put you on speaker phone so that we can all hear the answer?”

One year, we had one office needing to get back to us, one office that had a full voicemail inbox, and one in which the aid knew the exact number off the top of their head. This made a huge impression on my students and, again, it only took about 20 minutes.

Hold a Mock Election

Hopefully, you are able to teach a voting and election unit in the weeks prior to the November election. If so, a natural assignment would be to research select candidates and/or propositions that are on the ballot.

If you can get a sample ballot, photocopy it or recreate one with just the races and propositions on which you’re having students focus. Then on Election Day, make a big deal about it. Put up posters. Wear red, white, and blue that day. Hand out “I Voted” stickers. Again, this shouldn’t take more than 20 minutes.

As with registering to vote, though, make it clear that the act of voting is voluntary and private. After the election, compare results with offical returns, which can be found either on your county or state’s election site.

Write Op-ed Essays

Challenge your students to write their own op-ed essay relating one of your units to a current issue. Whether it is in your Foundations of Democracy unit evaluating how well America is currently upholding the ideals of the Declaration or Preamble with a specific current issue, in your Three Branches unit debating how government should solve a specific pressing problem, or your Constitutional Rights unit arguing if a sacred right has been violated recently.

As citizens on the verge of voting and heirs of the current political environment, your students are well-positioned to have their strong personal voices be sought out by newspapers editors.

In my class, I have students study the civics portion of the U.S. Naturalization Test. While, my state doesn’t currently require students to pass such a test, I do. So, I ask them what they think about it, because there is nobody more expert on this exact issue than them in this moment.

Over our semester together, while in the midst of studying for their big test, they research how many states do require it for graduation and the arguments for and against it, and then they write op-ed essays to submit to our local newspaper. If this sounds perfect for your course, my Citizenship Test & Op-Ed project kit is ready to go for you too.

Interview Others

One of my favorite projects each year is when my Civics students interview someone outside their immediate family about what democracy and civics mean to them. We do this as part of our Three Branches unit. I challenge them to select a person they don’t know very well on a personal level who holds a unique perspective—a senior neighbor who fought in the Vietnam War, the pastor of their church, a cousin who has been through the justice system, or a family friend who serves on a local elected board.

These are powerful experiences and the narrative essays they write are true treasures. Just a few months after this project one year, a student of mine lost her grandfather and if it weren’t for her interview, she and her parents would have never known certain details about his immigration and naturalization story. These are the moments teaching is made up of.

If you are curious to learn more, I have a whole blog post dedicated to how to successfully lead an interview project because I have seen it be so powerful for my students.

No matter how tight your scope and sequence are, I hope you can wiggle in some of these doable project ideas! The biggest barrier in not seeing government as a real, living thing is never experiencing it as a real, living thing. You’ve got to make it come alive. So, while having your students raise the flag at Fort Sumter likely isn’t an option, that doesn’t it’s impossible to make your Civics course real.

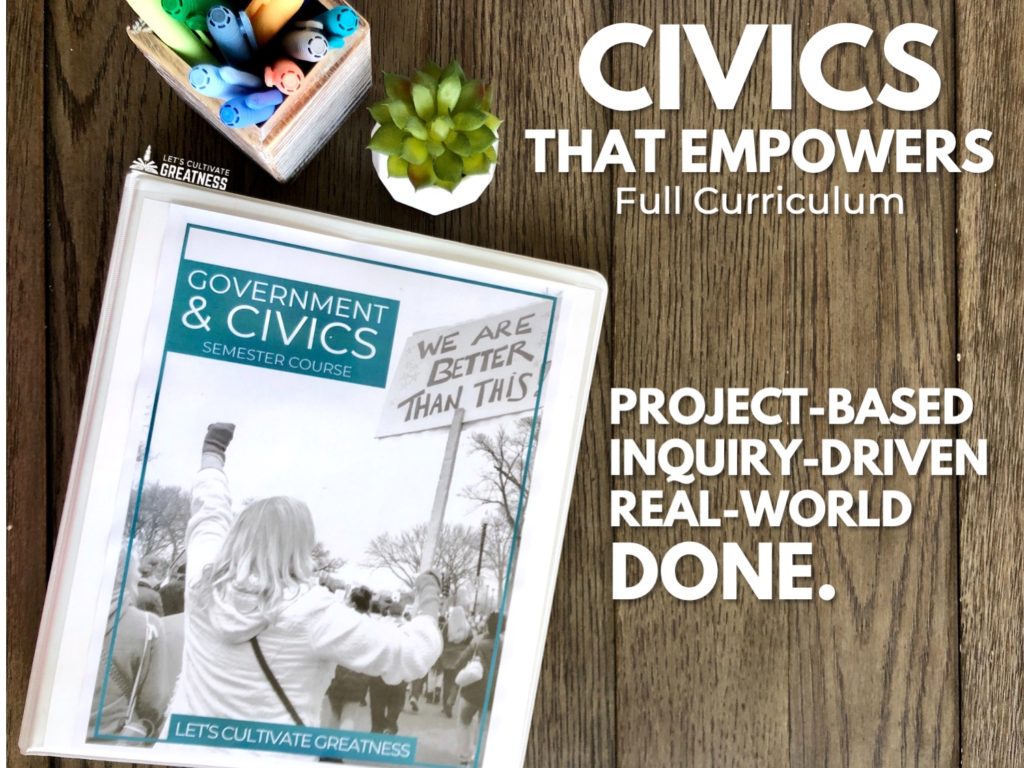

If teaching a project-based approach to Civics sounds like exactly what you are look for, I encourage you to check out my ready-to-go, everything’s done full-course curriculum!

Feature image photo credit: Taylor Wilcox, lowering of the flag at Fort Sumter, South Carolina