We know teaching writing in history class is important. But it can also be incredibly daunting to even think about how to weave it into your content-heavy classroom. So, we avoid it. Or save it for just one or two stand-alone essays, which is admittedly less-than-ideal for many reasons.

But what if writing was what students did every day in history class? Little pieces, single sentences, one day at a time? All of which were built towards a single essay question? And by the end of the unit, the essay would almost write itself in a class period or two—the same amount of time set aside for review and test days. It’s possible with some simple reframing of your history units, using some of the action tips below. I have come to structure my US History class (and my other classes, like Civics and Global Issues) to be writing-centered and I can’t recommend this approach more!

I don’t think I’m an extraordinary teacher, just one who found herself in the final days of her first year teaching being assigned AP US History for the following year. I had to learn how to teach effective, concise argumentative and analytical writing and learn it fast. Then, learn to fine-tune my approach year after year.

It was certainly a lot of work, but seeing big growth in my students fired me up. We’d go from disorganized and throwaway sentences to precise positions with unique insights as the year progressed. After a few years, I decided to transform my on-level history classes to be writing-centered as well, because on-level kids deserve the same access to high-level learning. The only difference is the need to go through the writing process a little more slowly and much more deliberately.

I’ll be honest. I fully believe I made the switch to taking all my classes to be structured on inquiry-based DBQ writing because I had to learn how to do it so early in my career and now I don’t know any other way!

Here, I want to share the why for this approach because, over the years, I have only found more reasons why writing in history class is not just more effective, but also more empowering for students. Plus, it even makes things easier on you! Be sure to read my blog post on how to create writing-centered history units first if you are still trying to wrap your head around what it even looks like; then come back to this one!

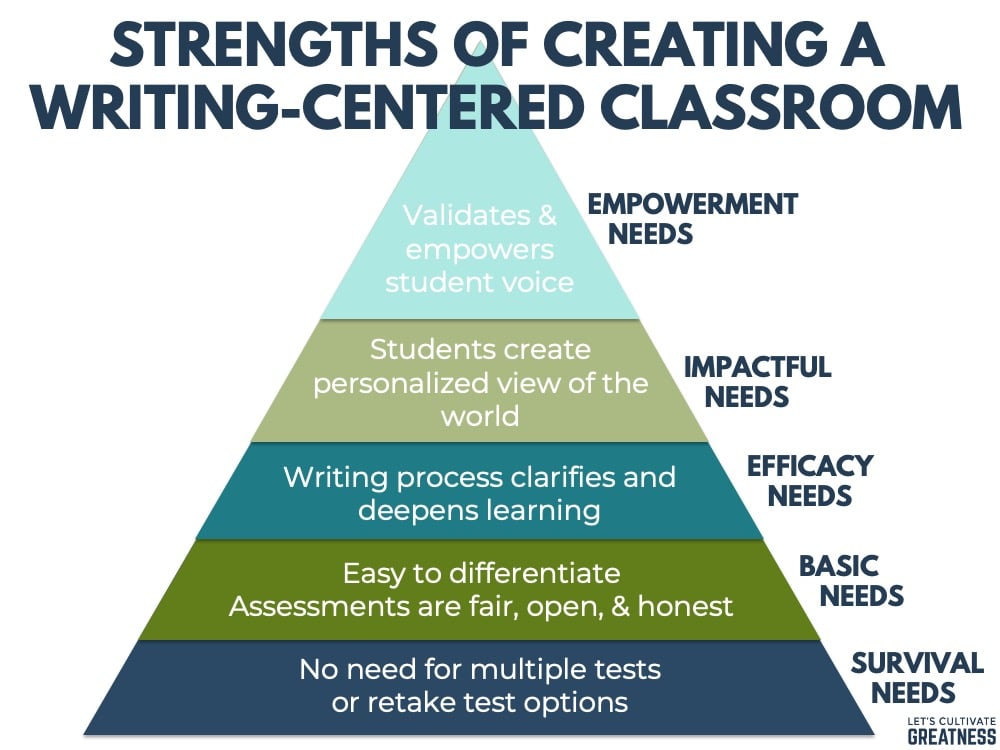

Writing offers so many logistical, pedagogical, and inspirational strengths to my students (as well to me!) that I think of it like Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs and I will never go back to traditional short answer or multiple-choice assessments again.

Essays Make Easier-To-Give Assessments

This doesn’t sound possible, but hear me out. When there is only one central inquiry question for students to ponder, creating multiple test versions, stressing over test security, and figuring out test retakes goes away.

Additionally, having multiple versions of a test or a large test bank imply that each individual question itself isn’t particularly important—they’re disposable and interchangeable—and yet students need to know the answers to them all. This ultimately creates an environment that communicates that knowledge is important only for the sake of passing the test. Not exactly why you got into teaching, is it?

Imagine a single question, known from the first day, that students work towards answering. In this scenario, test retakes are replaced with revising essays students have already started.

Also, essay assessments make unique situations a cinch. A student eagerly wants to redo their essay, but it’s the last day before winter break? Take it home and bring a revised version back afterwards. A student broke their arm? Have them dictate their essay to their computer. A student only did poorly on one body paragraph, but the rest is great? Have them rewrite just that paragraph.

For just these reasons alone, making an essay as your main assessment mode is worth it. It has made test time so much less stressful for both my students and me.

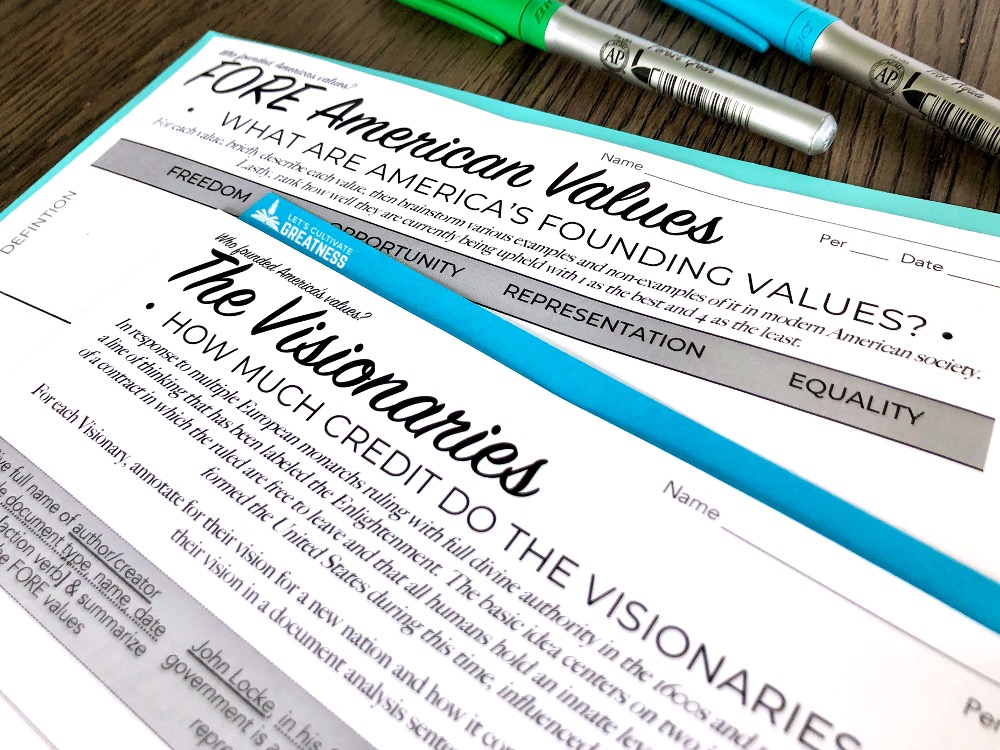

Action Tip: Put your unit question on every single sheet so students are always thinking about it. See this example from my America’s Founding Values unit, of how I put it in the upper-left corner.

Essay Assessments are Easier to Differentiate

You are able to meaningfully challenge all students. First of all, you no longer have to simplify test questions, develop leveled versions of your tests, or create completely different alternatives. When an essay is the main end-of-unit assessment, all of that goes away.

Instead, with scaffolding that you make available, like outline forms, thesis templates, and model sentences with plug-and-play options, all students have what they need. If a student comes up with phrasing that is better than the template, great! If they don’t, there is no shame or penalty in using the provided words.

For my lowest students, easy accommodations include letting students use their outline while they write their essay or giving them essay forms with sentences starters already included. And neither of these “dumb down” the task at hand. Rather, they raise the student up.

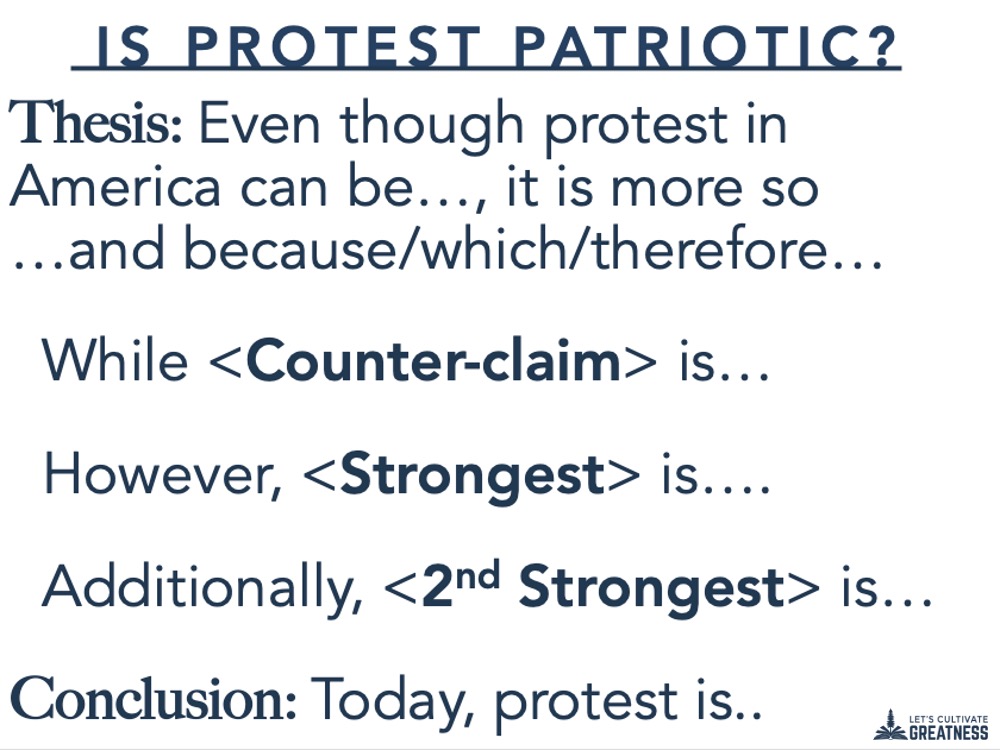

On Essay Day, I post a bare bones template on the screen while students write. All students thrive with this little nudge because staring at a blank page is stressful at any level. I also make skill sheets with generic model sentences available.

Advanced students love having these quick reference tools available as well, to raise their essay to that more nuanced level, which is exactly the support they need and deserve. Unfortunately, we often forget about or don’t make it as far as differentiating for our above-grade-level students, but essay assessments easily allow for just that.

Action Tip: Post a bare-bones template on the screen, just enough to nudge the pen or keyboard into action on Essay Day. Below is the slide I show in my Protest unit, in which we explore the complicated relationship between American patriotism and protest.

Essays are More Open and Honest Than Traditional Tests

When assessments are transparent, there is trust. Again, there is a greater sense of importance than the test itself when the test questions aren’t some big secret. When you show students the central question from the start, provide them a range of pieces of evidence to sort through and pick from throughout the unit, and guide them to their own answer using the evidence before them, they don’t view the assessment as some sort of “gotcha,” but rather as a natural culmination of their work.

Action Tip: At the start of your unit, spend 10-15 minutes talking about the question, what topics you will examine, why the question is so intriguing, and how you are inviting your students in to grapple with it.

The Essay Writing Process is the Learning Process

They say you remember only 10% of what you read, but 90% of what you teach others. It’s part of a widely cited adage, and whether or not the numbers are exact, as teachers we know they certainly aren’t too far off. When students have to carefully review their materials, thoughtfully declare a specific position, select the perfect adjective to describe it, then explain it to someone else, they have truly learned.

Students may think of the essay as the test to check what they learned, but really the essay is the learning. Over the unit, yes, they have been thinking about the content, but the outlining and writing process is when the real ah-has and magic happen. It’s only when you go back to view everything in context that pretty incredible ideas form.

No kind of traditional test can produce those results.

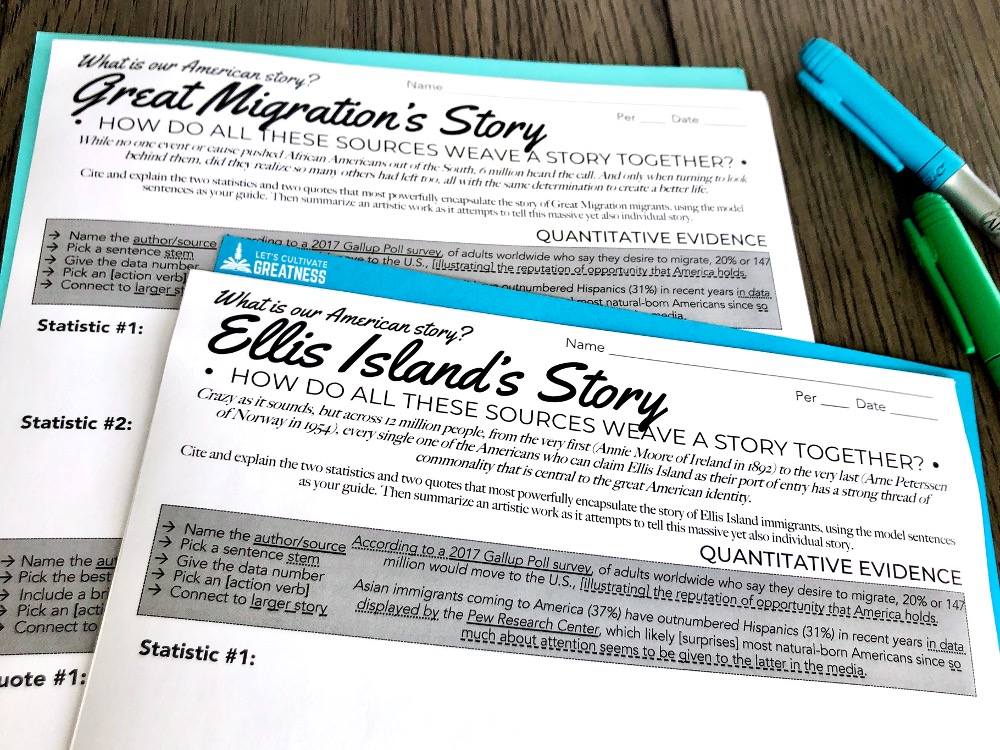

Action Tip: Have students connect each activity to the unit question through writing source-analysis and/or conclusion sentences. Then, on Outline Day, students can easily pull from all their pre-written thoughts. Below is an example from my Immigration unit, where students develop several high-level sentences for each immigrant group.

Students Develop Personalized Meaning of the World

Learning that is personalized is far more memorable and meaningful. The beauty of essay assessments based on open-ended questions is that there is no single right answer. The only right answer is what the student believes for themselves, so long as it is well-supported with evidence from the unit.

It is powerful to help students arrive at their perfect word choice. When they do, you see lightbulbs in their eyes. That’s why Outline Day is always my favorite day of the unit.

For example, one year as we were wrapping up our Immigration unit, one student kept coming back to the term “vigilant,” as in “we need be remain vigilant in appreciating our immigrant roots” and his essay took this angle. No student had ever made that exact argument before, and because it was his personal position, it was 100% right.

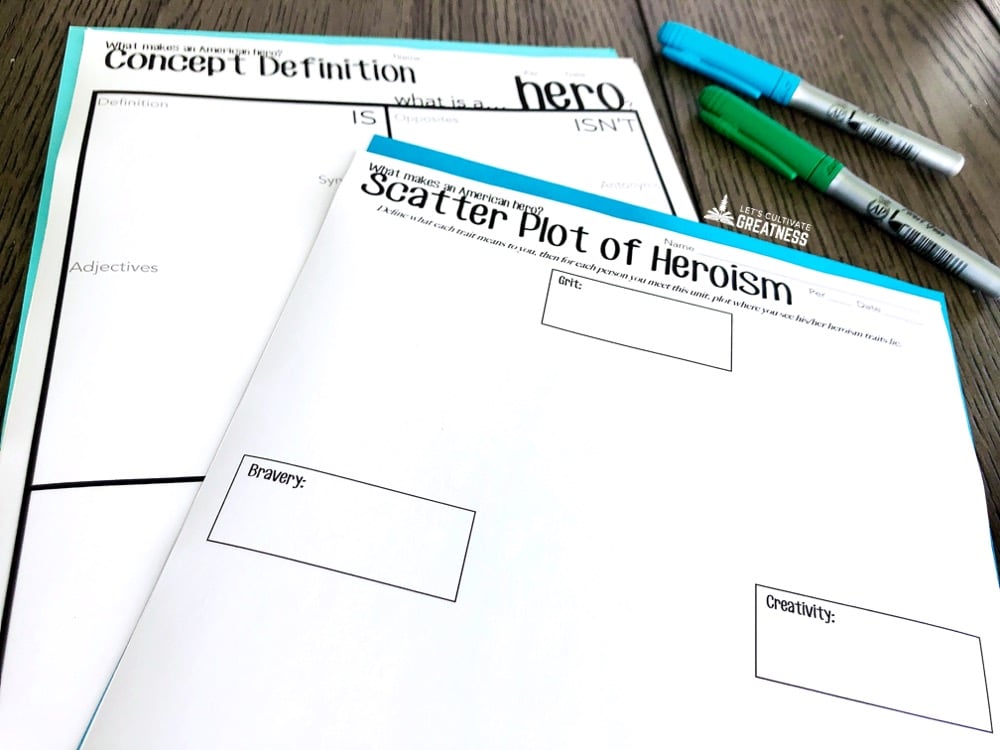

Action Tip: Write open-ended essay questions to allow students’ unique perspectives to shine. Communicate that the only right answer is theirs, so long as it’s well-supported and argued. Below is the notes sheet we use for our Hero unit, in which we explore a wide variety of people and events for a mix of four traits, allowing for all sorts of unique essays.

Students’ Voices are Validated

Empowerment is the greatest lesson we can teach. By framing your units to answer important central questions with no single answers, you are handing ownership over to your students, not just for knowing content, but for using their voices.

I repeat over and over to my students the importance of their voices, of speaking up when they have a perspective to share, and of having evidence to back up their claims. It’s easier to do than you might think. Simply talk about it when you assign a primary source from any commoner or activist. Those people had something to say, but, more importantly, they actually said it.

Action Tip: When scoring students’ essays, let your rubric score the logistics of the essay, so your words can be a place to leave meaningful comments (that can still be short!) that show you hear, wonder, or have next-step ideas about the thoughts they crafted. The score of the essay should never be confused for your validation of their voice.

A writing-centered history classroom will transform how your students think about the world and is a great framework on which to layer a thematic approach, especially one guided by a central inquiry DBQ-style question. I can’t overstate the way these three things—writing, inquiry, and a thematic approach—have upgraded my impact as a history teacher. Click below to learn more!

Feature image credit: Surface