All students need support in learning how to deconstruct an essay prompt. Whether it’s for an AP or on-level class, no matter now straightforward or complex the question, it needs to be broken down.

This skill of closely examining the prompt isn’t just the prerequisite for writing an essay, but it’s really the first step in cultivating the deep thinking that a history or social studies essay is meant to invoke.

The best way to think about social studies writing is centered around the idea that a focused and well-supported argumentative essay isn’t proof that learning has happened, but rather is an act of learning in and of itself.

That’s why this skill isn’t a teach-it-once kind of thing, either. It needs to be explicitly practiced with every essay.

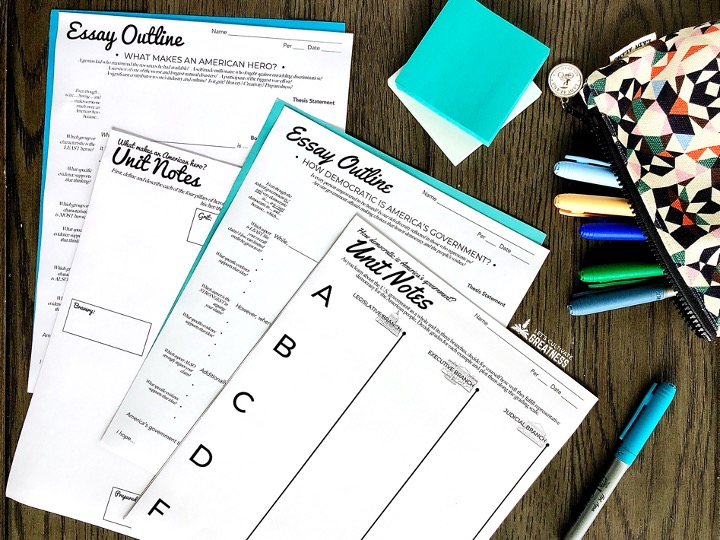

Deconstructing any writing prompt should be part of a larger essay outlining protocol you teach. Here, you can read my complete essay outlining process, in which I break down 6 distinct steps. Deconstructing the prompt is the first step of outlining and, since it has its own 4 parts, I’m diving into them here in detail to properly do them justice.

What I like most about these 4 questions is that they work for both history and social studies essay prompts. This allows for continuity across your whole department and for your students from year-to-year.

You should think of these questions as guidelines which should always be tweaked to match best with your particular essay requirements, especially if you are preparing students for specific state tests or AP exams. Be sure to create a handout guide for your students with the exact questions or steps you end up using.

Here are the 4 questions I use with my students to deconstruct essay questions:

1. What topics or content must I cover? What must I exclude?

This first question is particularly important if it’s an AP-style prompt with specific date ranges, or it’s a unit with a lot of content and the question is only asking about one aspect.

If you’re using my guide for creating inquiry-driven units then your unit will already be focused on a singular theme. However, it’s still important model this step.

Continuing with the example question used in my main essay outlining how-to post, “Was late 1800s America a land of opportunity?,” the unit focused on both the incredible wealth and oppressive poverty at the time.

So for this step you would make it clear that the question isn’t asking about, let’s say, foreign policy at the time, especially if that’s the topic for the next or a previous inquiry unit.

2. What’s considered true and not what I’m arguing?

This step is crucial in showing students how not to fall into the trap of summarizing or remaining at a surface level when writing their essay.

Think of truths as the broad understandings on which historians, political scientists, and other experts generally agree.

With our Gilded Age question, the truths are that two things—unbelievable wealth and poverty—existed simultaneously. So, take time to explicitly review with students they are not arguing there was wealth and there was poverty in the late 1800s. If they did that, they’d just be summarizing and not making an argument.

For another example, let’s look one of my Civics questions that asks students how well the three branches of the US government function democratically. The three truths we review are that there are three co-equal branches, the US Constitution lays out basic provisions for each, and that how they function today isn’t exactly what the Framers envisioned.

A student can absolutely make “a change over time” angle to their argument (and I certainly encourage that!), but if the entirety of their argument is that things have changed, then they are arguing something that is already acknowledged as a fact. Taking the time to tease out this distinction is important for students of all levels.

This also leads directly to the next two questions.

3. What skill must I demonstrate? How do I do that?

Is it a “change over time” or is it a comparison essay they need to write, for example?

If your class has a discrete set of essay prompt types, like an AP course, it’s especially important to display that short list for students to select from.

Once the skill or type of prompt has been identified, the second question must be clearly addressed. It’s easy to forget students need help making the leap from identifying the type of prompt to what that means they actually need to do.

Our sample Gilded Age question is a periodization question, which means students need to fall on one side of the fence or the other: yes or no. “Both” is not an option.

For a “cause or effect” prompt, it means arguing which one was the biggest cause or effect, because “all” isn’t allowed.

“Both” or “all” simply recaps the already-established truths and leads to summarizing, not arguing.

In my Global Issues course, I teach a unit on global diversity, both ethnic and socio-economic. Our unit-long inquiry is “Am I in the majority or minority of the world’s population?” This is a comparison essay prompt, so students need to decide between being more like or unlike others in the world.

Once I began making it clear that being on both sides of the argument is not an option, students stopped making that mistake.

4. What evaluation must I make?

This last question isn’t often written explicitly in the prompt, making it even more necessary to identify with students and train them to ask it of themselves before outlining their essay.

For example, in a “change over time” essay, the task is to argue which one was more. However, usually unwritten in the prompt is an implied and necessary “how much so?” and “was this good or bad?”

This follow-up question usually isn’t hard for students to answer when prompted, but they aren’t going to know to take that extra step if it’s not spelled out for them.

If you are teaching how to deconstruct an AP history essay, you’ll want to tailor this question to guide students into what’s needed to earn the “complexity” point, which can also include making connections to earlier or later historical events.

Most students simply address this implied part of the essay prompt after the “therefore…” or “which…” in their thesis. This is where the often-called “so, what?” part of the argument goes. Check out my go-to thesis formula if you are looking for one to use, especially one that teases out this final part.

If you are using open-ended inquiry questions for your essays, then your students’ evaluations will each be unique.

With our Gilded Age question, a student could conclude that the unprecedented wealth was a tremendously good thing, that the working and living conditions created were shameful, or that thanks to the work of certain early journalists, stronger regulations were made in the proceeding years. Endless options!

Next Steps

Having crystal clear answers to these four questions is essential in writing a strong essay, but it’s still only the first step in the support students need.

Don’t feel overwhelmed, though, because multiple steps is the point! Writing an essay is easy once it’s broken down into explicit mini steps. So, if you’re thinking, “… okay, what are all those steps?” I’ve got you covered.

Again, I shared my complete essay outlining protocol in another blog post, where I walk step-by-step through the handful of highly scaffolded micro-decisions that will lead your students to writing thoughtful, well-supported argumentative essays.

To see some of the writing-centered units I use with my mixed-ability social studies classes, click through the links below.

Check out my US History, Civics, or Global Issues courses if you’re interested in making essay writing central to your teaching. Both individual unit and full course options are available. Each unit includes all the essay writing supports you’ll need to scaffold writing like a pro—graphic organizers, outline forms, and how-to guides.

Feature image credit: via Deposit Photos