The ability to analyze a primary source document effectively is perhaps the most important critical thinking skill students should have walking out of your history class. But where do you even begin when there are so many types of sources and where do you find ones that will intrigue and engage students?

Those were my questions and that was my overwhelm when I was a new teacher. I was supposed to teach with primary sources, but I was also supposed to go out and find them on my own. I had no idea where to start!

On top of that, I didn’t really know what to do with all these sources once I found them.

Over the years, as my collection of favorites has grown, I can now confidently teach without a textbook, but to the new teacher out there now—I see you.

That’s why I’m sharing with you my go-to strategy to teach students how to analyze any historical document and my favorite place to look to build a library of great sources.

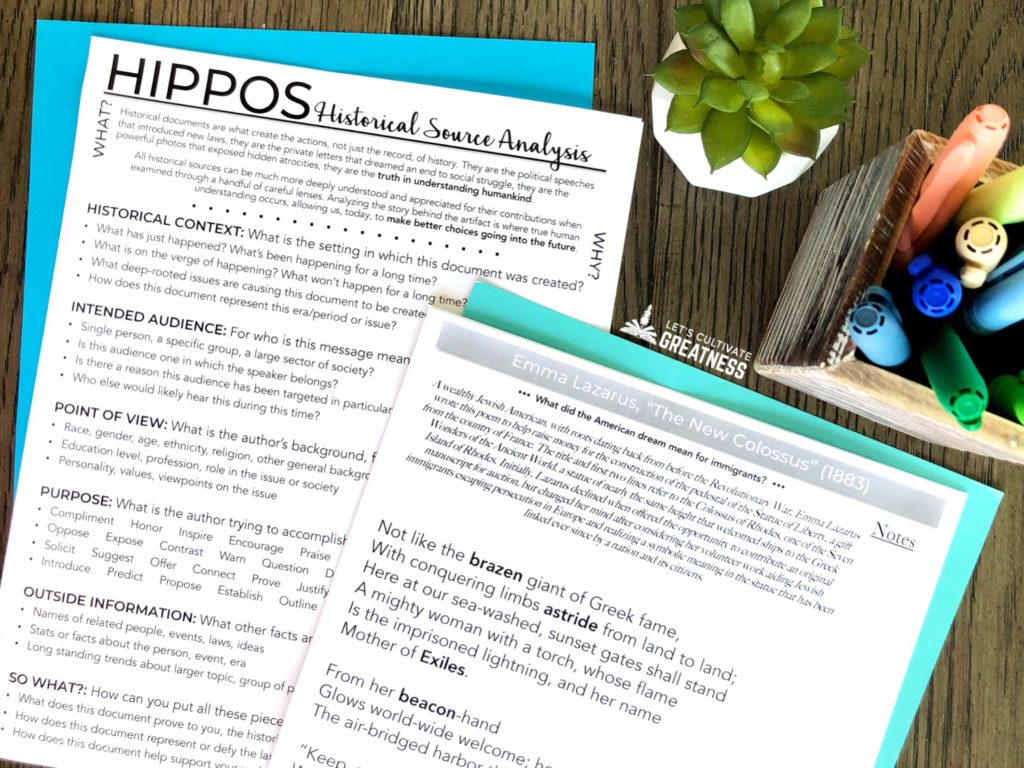

I love a good acronym strategy, and HIPPOS has got to be my favorite name. I have others for analyzing sources like news articles and poetry. If you want to check out the whole set, grab this FREE download with 6 different use-tomorrow document analysis handouts.

The HIPPOS strategy is specifically for written historical documents and works fantastically on everything from famous presidential speeches to obscure, intimate letters. I love how it is flexible enough to be used with any source!

Whether you are teaching middle or high school, on-level or college-prep, having a history course built on primary sources is a must for cultivating engaged and critically thinking students.

Before diving into the HIPPOS method, though, you first need to set your students up for success with these 5 tips:

1. Find great primary sources.

Easier said than done, I know, but there really are more interesting documents out there than inaugural addresses and Supreme Court decisions.

And it is crucial your sources serve up the human voices of men and women, white and brown, poor and middle-class, not just the edicts from those in power.

My best tip for uncovering lesser-known and intriguing sources is picking up a textbook supplemental document reader, which is the fancy term for an inexpensive paperback collection of sources organized to correspond with the textbook chapters.

If your textbook doesn’t come with this type of supplement, check out the ones that support Advanced Placement or college texts in your subject. Those are guaranteed to be robust and contain the lesser-known sources that are usually the best ones anyway. The two-volume collection, The American Spirit, by David M. Kennedy and Thomas A. Bailey, was my go-to in my first years of teaching US History. It led me to discover many rich sources that still remain some of my favorites to share with students year after year, like Jourdon Anderson’s letter.

2. Make clean, abridged copies.

Few sources are short enough to examine in their entirety (I’m winking at you, Mayflower Compact). My limit is one page. Sometimes, I have to use size 10 for ones that are just too good to whittle down any further, but I always stick to my hard rule of one page. And I’m talking about a single-sided one page.

Once you have a name and author, you can nearly always find a digital text of a source. Copy the text into your own file and edit out anything unnecessary. Class time is too precious for students to read more than they absolutely need to, and one page is instantly perceived as a manageable length by students.

3. Predict students’ questions and misconceptions.

Spend a few minutes thinking about what contextual knowledge students will need to know, or incoming misconceptions they will have about either the source or the historical topic. Often when I do this, I realize there’s something I need to quickly fact-check or there’s a question I need to look up! This information will be exactly the details you will share out during the “Outside Information” section of the HIPPOS strategy.

4. Define any academic words.

Part of what makes a certain primary source worth analyzing in class is its presence of rich word choices, giving your students the opportunity to see academic language “in the wild,” but not to be such advanced writing that it is difficult for students to comprehend the message. The perfect source will have a handful academic words worth spotlighting, but otherwise be accessible to a high school reader.

As part of your lesson preparation, skim through and mark those words by putting a box around them or bolding them prior to assigning. Then, have student crowdsource the task of defining these words together prior to reading.

5. Provide an annotating task.

This is where providing engaging contextualization prior to students reading the source is crucial. Give a teaser for what they are about to explore. Pose a wondering. Leave a gap in knowledge that the source will answer. You not only are enticing your students to be on the hunt for content, but also to be looking for that secondary component.

Phrase your annotating task as a question: What reasons does the author give for his/her position? How does the author describe the situation he/she sees? What outcomes does this author want?

Now, you’re ready to use the HIPPOS strategy!

This is my go-to for any historical written source in my classroom. After reading a source through, we reexamine it through these handful of lenses. Here are the basics of the HIPPOS:

Historical Context

What events have happened already? What events haven’t happened yet?

Intended Audience

Who is the source meant for? How does the author speak to them?

Point of View

What role in society and perspective does the author hold? What adjectives can be used to describe them?

Purpose

What objective does the author have for this audience? What are they trying to accomplish with this source?

Outside Information

What are a few crucial facts that need to be known to better understand this source? (This is the part that I provide students before we read)

So What?

How do all these things fit together to connect the source to historical events in one consolidated sentence?

The best part is how this framework builds students up to craft high-level analysis writing and to pull essential quotes from the text, which are the exact skills needed to prepare them for our end-of-unit DBQs essays.

I can’t recommend this strategy enough for exploring primary sources with your history students!

Click below for your FREE download!

Get your own HIPPOS skill sheet and 5 more print-and-use strategies sent directly to your inbox.

Feature image credit: Syd Wachs