The document-based essay is hard. Hard to teach. Hard to learn. But that’s because it’s the culmination and synthesis of all the historical thinking skills in one.

So, we leave it to the end of the school year to practice. Or we let the Advanced Placement and honors classes tackle it. But what if we did it differently?

What if we started the year with teaching the DBQ essay? What if the DBQ essay was the curriculum for on-level courses? What if the DBQ format was used to invite in below-grade students to historical analysis and argument?

Teaching students how to write a thesis-driven argument, supported by facts and primary sources, isn’t as cumbersome as it sounds. Instead, it can be a great framework for creating your units!

After teaching AP US History for a few years, I realized my on- and below-level students deserved the same challenge in their regular US History class. I knew they had potential to demonstrate all the same skills, they just needed a little more time and scaffolding.

So, over the years, I developed my regular US History units (and now my Civics and Global Issues units, too!) to be entirely DBQ-framed: we open the unit with our question, we analyze sources as our unit activities, organizing what we’ve learned as we go, we set aside a dedicated “outline day” to form our arguments and find our evidence, and then we write our end-of-unit DBQ essays.

Unlike a sight-unseen, 60-minute high-stakes essay, which is the capstone of the College Board’s AP history exams, a DBQ unit works on the essay over the course of a few weeks and written over a few days so you as the teacher can support students at every step. This makes them doable even for students well below grade-level. How awesome is that?

Over the years, I have also added layers of a thematic approach as well as a PBL structure to my on-level US History course, but it’s not necessary to still create a high-level experience that is accessible to all students.

Here are my best tips organized into the three stages of a teaching a DBQ unit: planning your unit, teaching with primary sources, and writing the essay.

Planning a DBQ Unit

Craft a short, yet open-ended question. There is no getting around needing the perfect question before anything else. It can be a question with a clear historical thinking skill, like change and continuity. For example, “How much did the role of government change in the lives of Americans during the Great Depression?” Or it can be one that raises an enduring theme, like “How successful were minorities and women at gaining greater equality during World War II?”

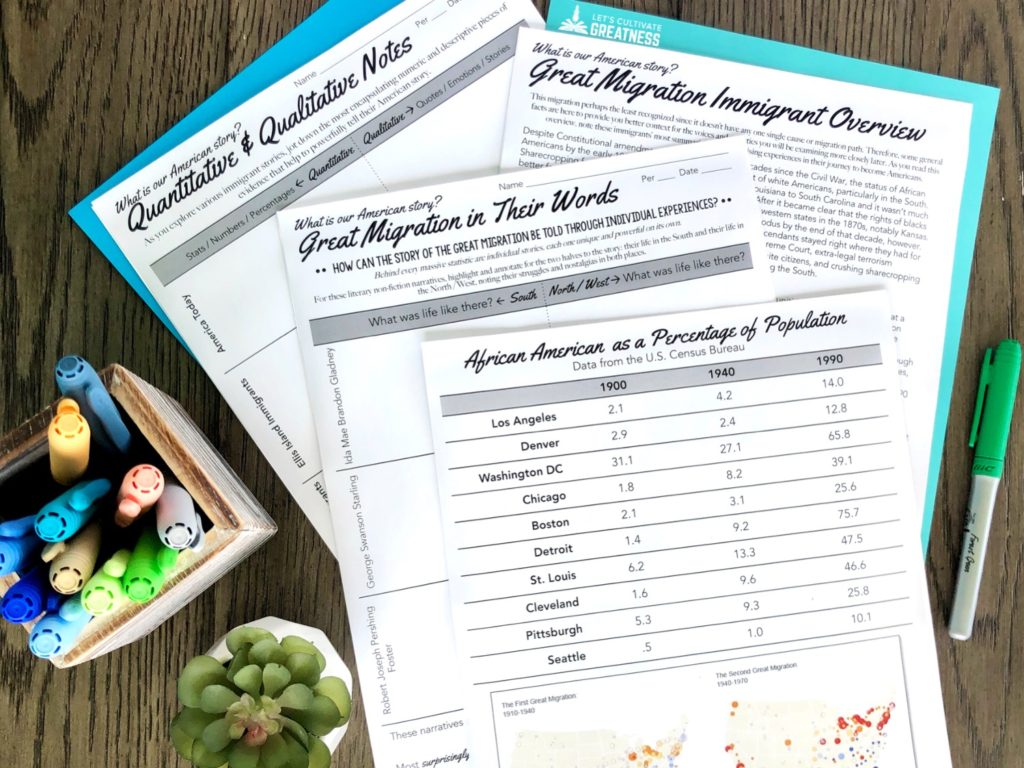

Keep the question direct and simple. I make mine super short. My immigration unit is guided by the question, “What’s the American story?” It is so short because we focus extensively on idea the that immigrant stories define the American story.

Most importantly, you don’t want to turn off students, especially your lower-level students, with a question they can’t even understand what it’s asking! I further detail my question brainstorming process in another blog post, if you want more tips.

Pick intriguing and well-rounded primary sources. These are the foundations of your unit activities. Choose a variety of sources that are written and visual, audio and video, public and well-known as well as private and obscure, and that incorporate different points of view, including people of color, women, immigrants, and lower socioeconomic classes. I have had good luck finding great ones in the primary source readers that accompany AP or college texts. As a general rule, I use excerpts no longer than a page, at most. I have a whole blog post dedicated to my best advice for more effectively teaching primary sources.

Gather necessary outside information. Ask yourself what students need to know about the topic to balance and contextualize the documents and decide how you want to deliver it because DBQ units likely need more tailored content than what is in a covers-everything-an-inch-deep textbook.

I prefer mini backstory lectures prior to activities and brief background readings for students to annotate. Having a “lecture day” at the beginning of the unit with guided notes for students works well too.

Teaching Primary Source Analysis

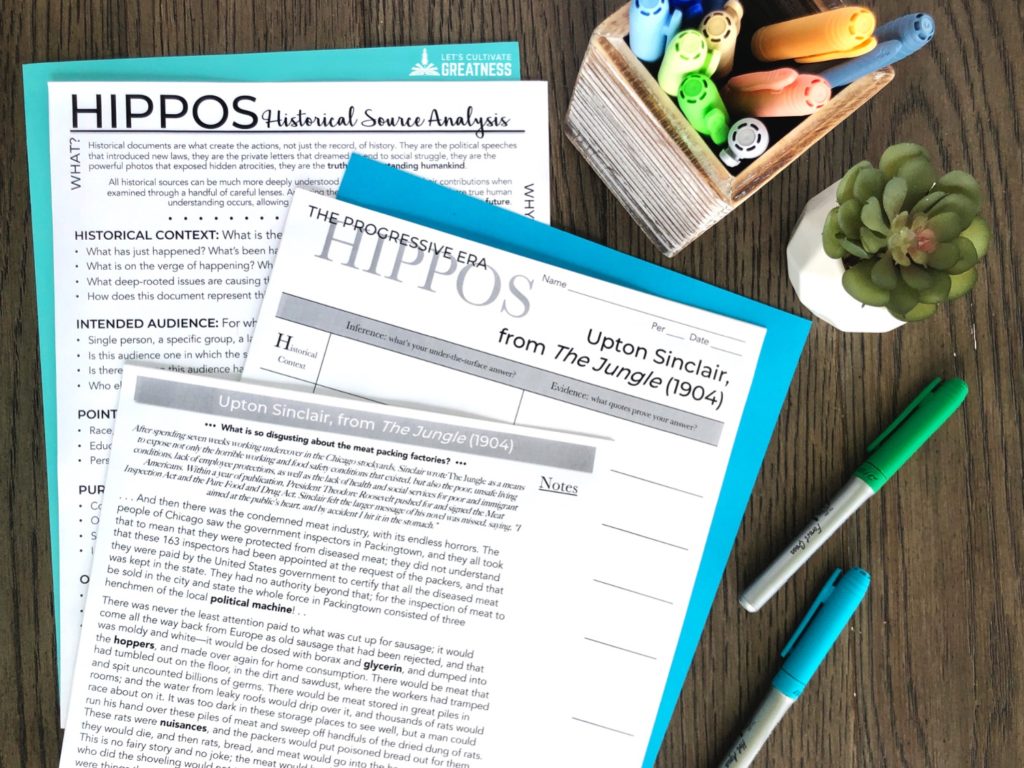

Ask deep questions about the sources. Ask students “why would” instead of “why” and “how can” instead of “how,” and have the students work together to develop answers with quotes to support their thinking. Ask about the author’s perspective on the topic, their motives in creating the source, and who their audience is. And give students reference handouts with word banks and analysis strategies to consult. This is key!

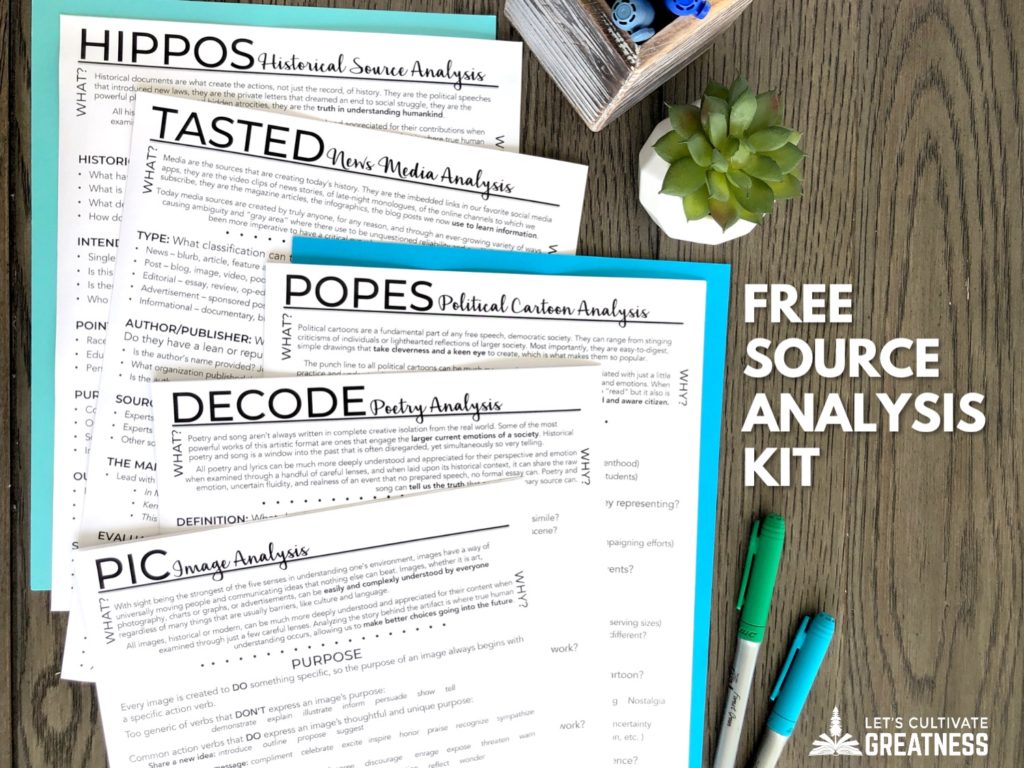

My favorite is the HIPPOS historical document strategy. If you want a copy for yourself, along with handouts for four other types of sources, download this free source analysis kit to start using in your classroom tomorrow.

Create a graphic notes organizer. Also support your students with a notes sheet that visually matches the historical thinking skill being asked of them. This is crucial for making higher-level thinking accessible to below-grade level students!

For example, if it’s a compare and contrast essay, provide students a Venn diagram to add to at the end of each class. If it’s an evaluation “how much…” essay, provide a continuum line.

Constantly circle back to the question. Don’t write and forget it on the whiteboard; refer back to daily. If the question is about the effectiveness of Progressive Era reforms, then challenge students to assess how this person or that group created positive change with each new document. Repeat the question, rephrase the question, ponder the question all unit long. I even put the question on every single worksheet and on my daily agenda slides!

Writing a DBQ Essay

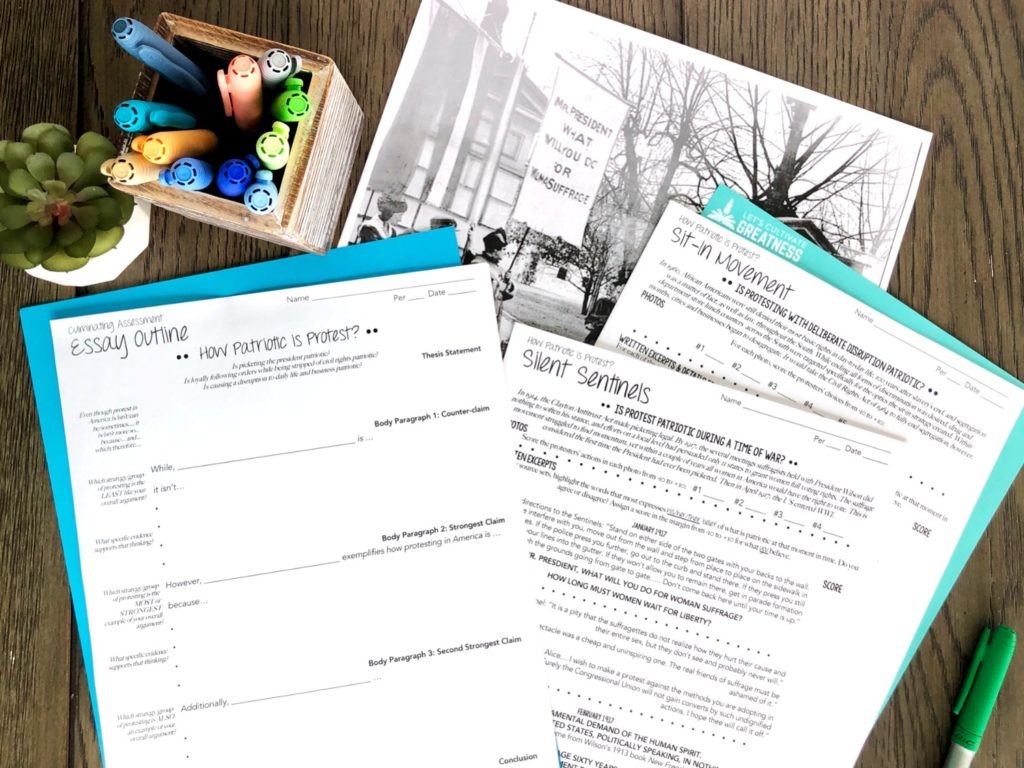

Break down outlining into singular steps. The switch from learning to demonstrating learning is often where kids get tripped up because that’s when the scaffolds ends. But in an on-level course, you must support students to the end. One way to do this is through a three-step process at the beginning of the essay outlining stage.

First, students pick their side: more continuity or more change, more effective or more ineffective, etc. In the case of my protest unit, students commit to an amount word: extremely, occasionally, rarely, etc. Second, students pick the two categories (or reasons) that best support their side. Thirdly, they pick one category for the other side to be used in their counterclaim. One, two, three discrete steps done one at a time as a class. Then, and only then, do students begin filling in their outline form. And, absolutely provide an outline form!

Insist on a strict thesis formula. For years, I have used the Even though X, A and B, therefore… template with great success, where X is the counterclaim paragraph and A and B are the two supporting body paragraphs. As much as we think formulaic writing isn’t the writing we want to teach students, we ignore the fact that many kids struggle to write well without a formula.

So, I tell my higher-level students to build off the formula and reassure lower-level students they can use every bit of the formula at no penalty, but no one gets to write lower than it. And this formula is the exact one taught by many AP teachers anyway. Same level of thinking, only slower and more supported.

Provide sentence starters. Whether your students are typing their essay over a couple of days or writing it timed in class, staring at a blank screen or paper can paralyze and actually interfere with them demonstrating the content they know. Give them this tiny nudge of thesis, body paragraph, and conclusion sentence starters. I post them on the screen on while they write, and it completely eliminates blank papers or wildly unstructured essays as a result, which is about the biggest win-win I could ask for as a teacher!

You’ll be amazed what your on-level students will be able to master in a DBQ classroom, with just a little extra support, like sentence starters and analysis reference guides!

A DBQ classroom is also a great framework on which to layer project-based learning and a thematic approach. I can’t overstate the way all three have upgraded my impact as a history teacher, but it starts with a foundation of primary source analysis. Click below to have my free kit of 5 tailored analysis handouts sent to your inbox, which includes the awesome HIPPOS historical primary strategy, and start upgrading your teaching tomorrow!

Feature image credit: LinkedIn Sales Navigator