Any history teacher knows that a primary source-based course is the best way to teach the stories and lessons of the past in a way that’s both rich and intriguing.

But….let’s be real. You can’t just assign all this reading and expect expert-level analysis like it’s a college class. Part of the joy of teaching middle and high school students is providing them the type of scaffolding that breaks down big ideas and dense words into something relatable and meaningful.

So, what are some different ways to do that with a variety of high-level sources?

This was one of my biggest questions my first several years of teaching. I felt like as soon as I discovered a new method, it quickly became overused simply because my history teacher toolbox was so limited.

Over the years, I developed several strategies that I can now pull from to match with a particular source exactly with my goals in analyzing it. Here are five of my favorite and most-used ones from my classroom.

Search for a Central Theme

This is a must for anyone wanting to create a more thematic approach to teaching history.

Even if you aren’t teaching fully thematically, you should still have a central theme to each unit as a way of examining and connecting your primary sources. If you are interested in ditching the chronological format, check out this blog post where I detail the steps for building thematic units.

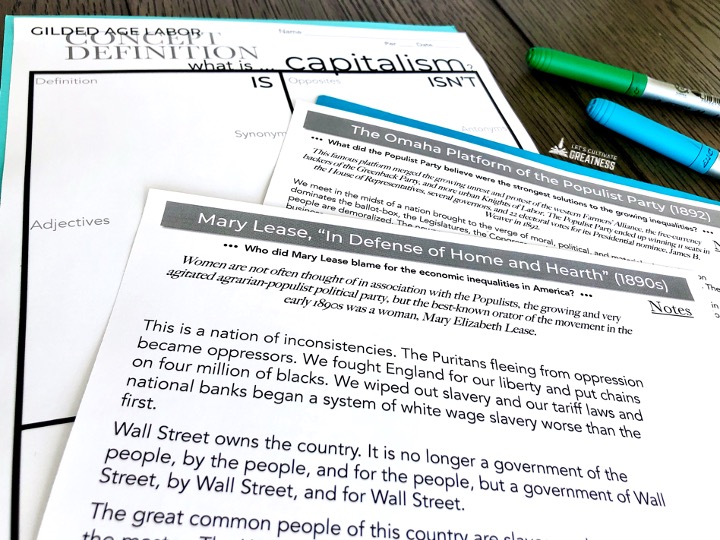

Regardless, no matter the topic or era in history, there is some central theme: democracy, equality, progress, etc. The theme could also be more specific to that era: containment, Vietnamization, or Double V. Throughout the unit you should be talking about it, challenging what it is and isn’t, then when reading a source, asking students to read for, essentially, how that person saw, defined, or exhibited that theme.

For example, you could use the idea of “modernity” to frame a station activity with short excerpts from various 1920s sources, like the Scopes Trial, a news article on Charles Lindbergh, a speech from Margaret Sanger, or advertisements for Model Ts and household appliances.

When I taught AP US History and we had to cover seemingly endless content, this greatly helped my students find meaning in and connection among sources in a quick, yet impactful way. That’s why all my primary source 6-packs group a variety of sources around a central theme or concept. Check out Volume 1: 1600 Through 1900 and Volume 2: 1900 to Present for a year’s worth of US History primary sources, all curated to connect to broader ideas.

Look for Persuasive Devices

There are multiple ways you can focus a single or collection of sources by analyzing in search of their use of persuasive devices.

Nearly any source, but especially those created by activists, incorporate some amount of emotional, logical, or authoritative persuasion. So, after a quick lesson on pathos, logos, and ethos, have students look for these elements. Sometimes sources use elements of more than one, which makes for a great discussion.

This also makes for a great way to frame a whole unit. In my thematic unit on American Values, we examine how it’s been activists who made the nation’s founding values, like freedom and opportunity, actually come to fruition in America. In it, we think of the activists’ writings through the lens of their ability to persuade for change using pathos, logos, and ethos.

For example, after we read excerpts from Benjamin Banneker’s letter to Secretary Thomas Jefferson and Frederick Douglass’s “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?” we consider and compare their words for their persuasive techniques. Certainly, both take on an ethos appeal, speaking first-hand from their experiences as oppressed Black men, but Banneker adds on a layer of logos while Douglass veers more toward pathos.

If analyzing a work like a presidential or other speech famous for the oratory skills on display (so pretty much anything from Dr. Martin Luther King!), you can certainly tackle more specific persuasive and rhetorical devices if you’d like.

By looking at a source through this lens of persuasion, you can take the discussion to the next level asking students about the effectiveness of the techniques used and draw comparisons with other historical or modern examples.

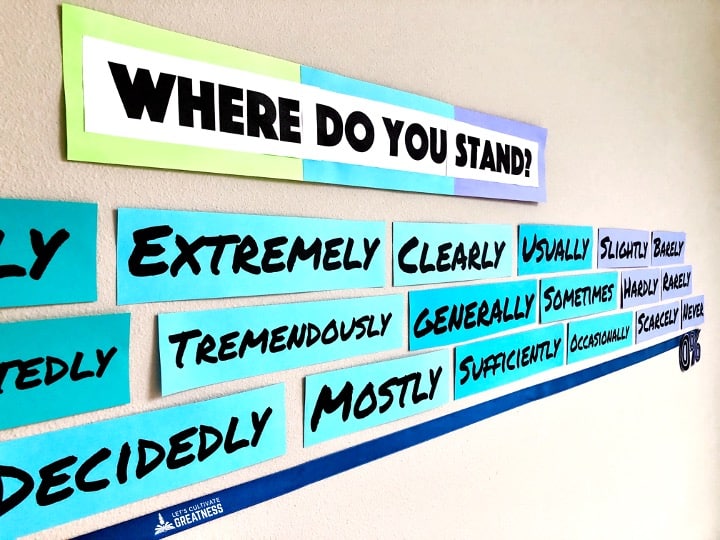

Score Along a Continuum Line

This takes the “central theme” strategy to the next level. Instead of just asking where a theme is present in a source, which is still totally worthwhile, you can elevate it when you also ask this one simple question: “How much so?”

“How much or little is that author exhibiting whatever central concept or idea?” “How effectively is the author using persuasive devices?” “How much does this author agree with another?” The possibilities are truly endless, but, no matter the question, the idea is that students pick a single amount word to stake their claim along the line “infinite” options and find a quote or two of evidence to support it.

I detail how I have turned this simple question and continuum line approach into a cornerstone component of my classroom in another blog post, so head over there to learn more.

Pick Apart the Organizational Structure

This works best for longer speeches or essays, like a presidential speech or an essay with several parts like Andrew Carnegie’s “Gospel of Wealth.” Have students draw boxes around sections, number paragraphs, highlight for the thesis statement, etc. all right on the source. I love using this a few times throughout the year to remind students of the core organizational components of effective writing, while also showing how these rules can be tweaked when done well and carefully.

This strategy is a must if you ever have students read an op-ed or other modern writing sample.

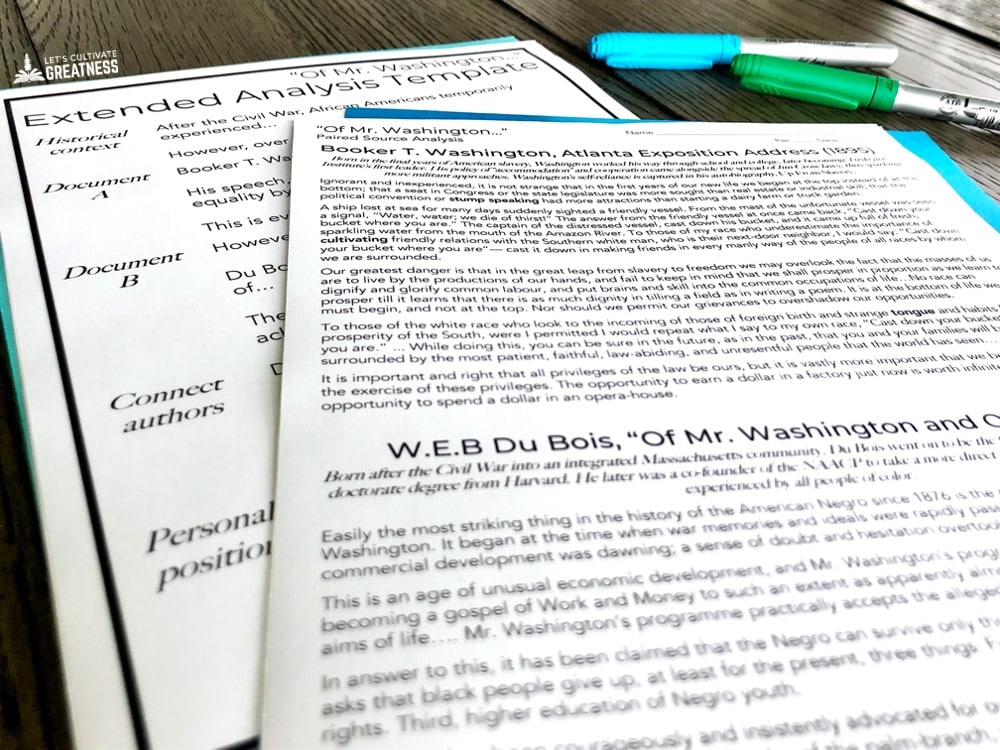

Pair Two Different Perspectives

Presenting short (half-page or so—seriously, not very long!) excerpts from two opposing or complementary sources is a fantastic way to show how history is entirely about multiple and usually not-completely-agreeing perspectives. But unlike a typical DBQ essay that can overwhelm students with half a dozen sources, two is totally manageable.

Some famous pairings are, of course, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois as well as President Jackson and the Cherokee people. However, also consider presenting points of view that aren’t in total opposition, like President Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms speech and Norman Rockwell’s subsequent paintings of the same title.

Before examining the sources, have students discuss the central issue and reflect on why there could be disagreement on it or how peoples’ backgrounds color their beliefs. Or in the case of the Four Freedoms, think of modern examples of how the words or actions of one person have inspired others to act.

Then have students examine the sources looking for those differences as well as similarities and points of agreement. I outlined this paired source lesson framework in 5 easy steps if you want to learn more.

Paired sources work great at the beginning of the year in building up to more-involved DBQ work or whenever you simply don’t have the time to dedicated to a collection of sources.

I have several of my favorite paired sources in my shop for easy plug-and-play US History lessons. Each weaves together student discussion, “close” analysis, and high-level writing all in one class period.

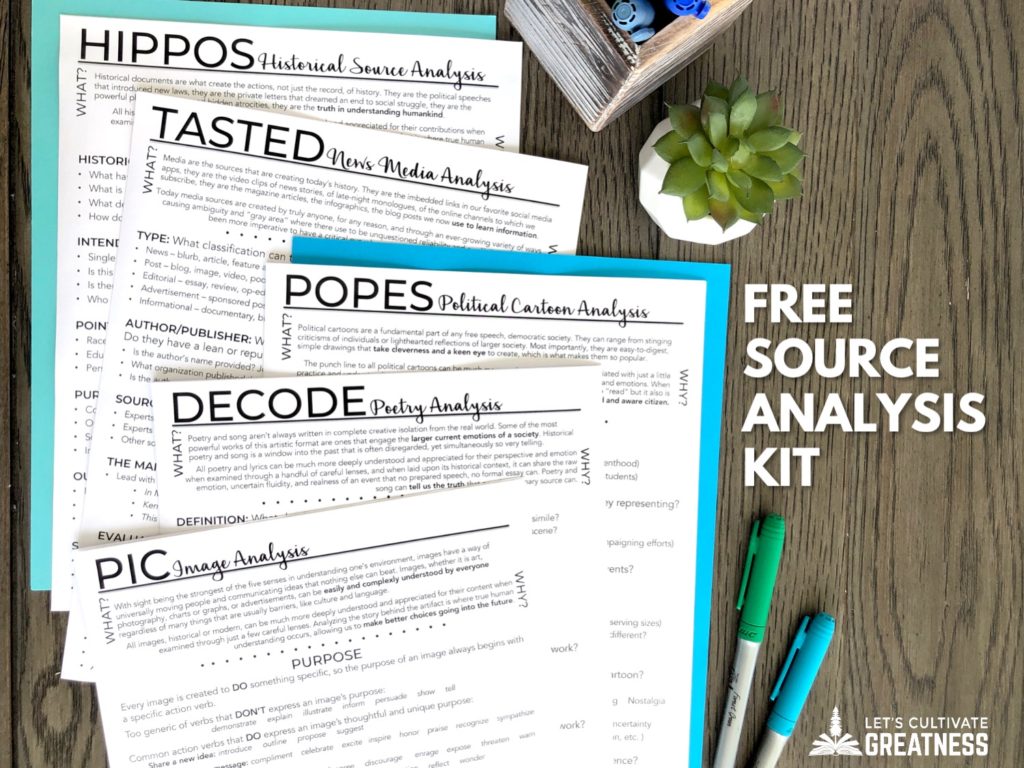

I hope these approaches have given you new ideas for your history teacher toolbox. If you are looking for more plug-and-play primary source analysis ideas that can work with any document, then you’ll love my Primary Sources Simplified Kit, which is a FREE download of five tried-and-true strategies. Everything from writing and art to political cartoon and news articles are included.

Feature image credit: Jeswin Thomas