Project-based learning has been experiencing a bit of a spotlight for the last few years. Heck, even Bill Gates put a PBL-praising book on his 2019 recommended book list. But when you really look at the core tenets of the pedagogy, it’s really just an acronym rooted in good teaching practices.

Unfortunately, a lot of the success stories touted by experts come from non-traditional school settings, making it difficult to understand how PBL can fit into a regular classroom. Additionally, they are stories, not step-by-step blueprints and certainly not any ready-made kits.

So how do you actually do PBL as a classroom teacher in a regular ol’ public school classroom? What about specifically in social studies?

Believe me, I’ve been there, wondering how to make this great-sounding approach work for real in my US History and Civics classes. I’m not a PBL trainer, I don’t work for a consulting company, but I am in the classroom, self-taught with a few PBL books on my shelf and with several years of trial and revision under my belt. And I want to share my successes with you.

My project-based learning journey began November 9, 2016, the day America woke up to the outcome of one of its craziest presidential elections and shared a collective bewilderment. A lot of people were asking a lot of good social studies questions: Did the Electoral College function as the Founding Fathers intended? Did we get hoodwinked by fake news and ads? How did we come to be persuaded more by emotions than the issues and facts?

As a high school U.S. history and civics teacher, I took it personally. I felt that I somehow failed in my duty to teach content and skills with enough relevance to create empowered citizens. In searching my soul and Google for the answers, I landed on project-based learning.

Instantly, PBL spoke to my desire to be a more effective teacher. Instead of putting an impossibly long list of standards and a state test at the center of my classroom, it switches the paradigm and holds authentic learning as the cornerstone.

But I was left thinking, “That sounds great! But… how would that actually look in my classroom and where would I even begin?” These are probably the same questions you have right now so, welcome! You are right where you need to be!

This guide answers the most common questions I get from other social studies teachers who are PBL-interested but still seeking real examples and action items to go along with the “textbook” explanations. Here we go!

What is Project-Based Learning?

Textbook answer: PBL units are propelled by a laser-focused driving question that requires specifically chosen key content and skills to arrive at the answer or complete the challenge. To get there, students gather and work with that content to arrive at the goal, which is an authentic end product. Everything is tightly woven: the question, the content learned, the end product, and the purpose.

Been-there answer: The first step is determining the key content and skills for the unit—what I want to cover in-depth, which really spoke to me as a history teacher who never could cover all the standards. Does anyone?!

Depth means understanding and 180 hours is already not enough time to do the history of the United States justice. We have to be able to make hard choices about prioritizing key take-aways for our students’ long-term health as citizens.

I now skip over WWI with no regrets. Are there great lessons to be learned from the Great War? Of course, but it now is a deliberate omission, not a source of “ran out of time” guilt. (In full disclosure, my students don’t have state-mandated end-of-course exams and I have the blessing of my principal.)

I want students to walk out of my room with a grasp of certain things that they’ll never forget. Of course, all teachers do, but finally I feel that PBL allows that to be more possible. I’m more effective, invested, and energized because of this shift. Depending on the level of autonomy you have in your classroom, what you can cut and what you can deep dive on will be different. Hopefully, you can find wiggle room somewhere.

Second, which works simultaneously with the first step, is developing an intriguing, open-ended question or challenge for students for students to solve. The key content and skills are directly needed to answer the question or complete the challenge. The PBL people at the Buck Institute call them driving questions. Call them what you want, but a great curiosity-inducing wondering or a just-out-of-reach challenge is going to clarify, focus, and entice your students better than without one. And because humans are innately curious creatures, learning is measurably improved by framing it as question.

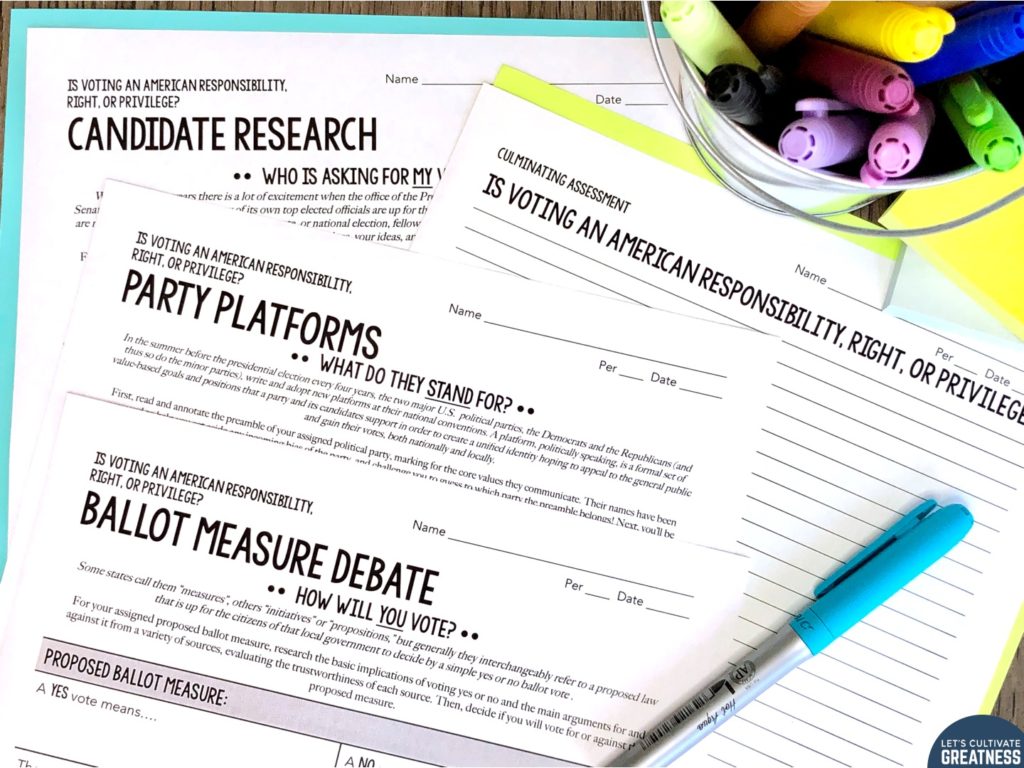

I have found success in developing my unit questions around points of contention and hypocrisy in our complicated history and current state of American democracy. For example, “Is voting an American right, responsibility, or privilege?” for an election unit, or “Who really founded America’s values?” for an early nation unit.

Every activity, reading, image, and fact we cover in the unit contributes to answering the driving question. This means that my students already know the “why” for what we are doing every single day. It helps that I also put the driving question on top of every day’s agenda slide, the white board weekly calendar, and every single activity 🙂

Question for you: What’s an intriguing, open-ended question you could pose that would serve as a guide for an upcoming unit?

How do PBL projects differ from traditional class projects?

Textbook answer: Yes, there really is a fundamental difference between the two. PBL is a shift of thinking about what a “project” is and what its role is in the classroom. The Buck Institute give a great analogy that a typical classroom project is often treated like a dessert—something done after the content has been learned and assessed. PBL thinking is that the project should be the main course—the driver for content. PBL projects create better student buy-in than regular class projects and have students craft real-world skills that are embedded into the nature of the project because the project is for the real-world.

Been-there answer: I don’t go as far as to treat the project AS the unit, though some PBL purists do.

In a PBL setting, students work on the project throughout the unit. I set it up so that between each segment of content, we weave in one step of the project. That way the “why” for learning the content is crystal clear—to be able to complete the next step of a meaningful end product. The two are not unrelated concurrent things. The content creates the foundation on which the project builds, and the unit question drives the project.

The project that students complete over the course of the unit is authentic in purpose and audience. This means students aren’t making a diorama of geographical features or a fake newspaper article of a historical event to present to each other. They are creating something (anything!) of larger value and delivering it to someone beyond their classmates and me.

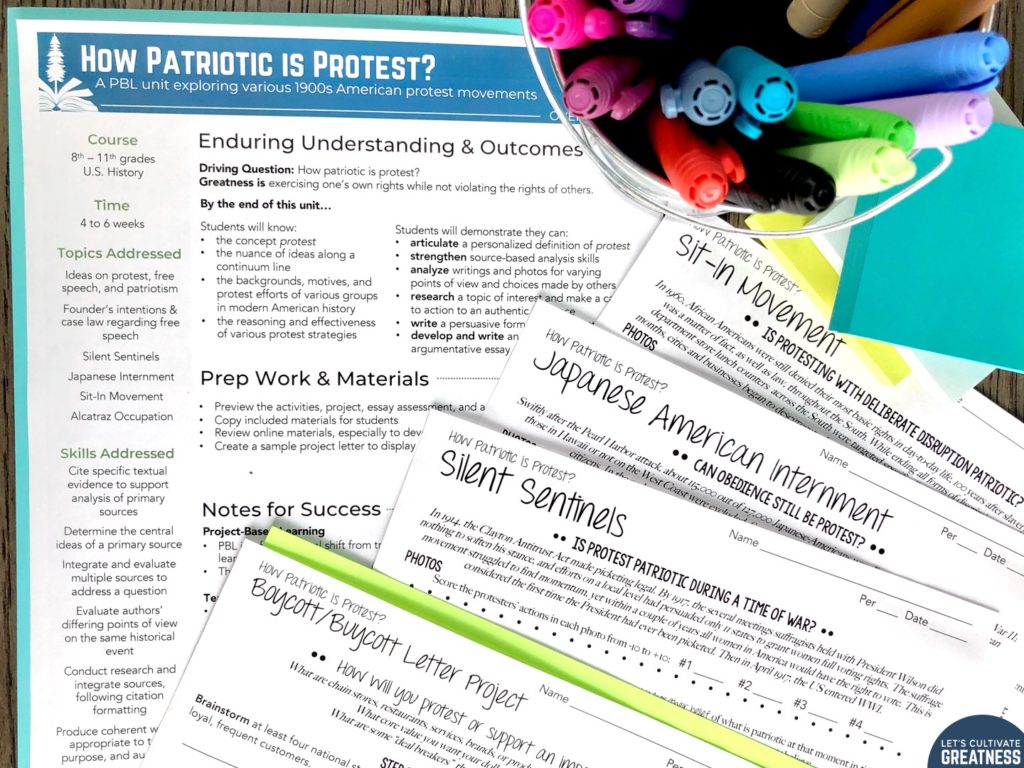

For example, we learn about various protest movements in American history by evaluating the effectiveness of their arguments and strategies so that when students create their own act of protest, they are more likely to have their message heard because they have modeled theirs after the successes of activists who have come before.

A key feature of the end product is that it is clear that I am not the audience. I grade their letters of protest, but then mail them off to who they are truly meant for. And, thankfully, my school is happy to pay the postage. The projects’ real audience always receives the finished products.

By being undeniably realistic, a PBL project frames everything within the unit then as automatically genuine, too. I see the projects we do spark a genuine curiosity for learning in my students that I didn’t see before.

Question for you: How can your students engage with the outside community in a way that’s related to your unit?

What makes a great PBL project?

Textbook answer: PBL projects make wishful takeaways a reality, as students acquiring real-world skills help solve real-world problems. They should be relevant and meaningful to students.

Been-there answer: Looking across one of your units, what one thing do you wish kids got, really got, as the big takeaway?

A novel study where one of the main themes is kindness? A geography unit where you stress all the beautiful physical features America can call their own? A history unit in which you challenge student to see negative, as well as positive, impacts of technology?

I bet even now those questions have given you the seed of a really cool PBL idea.

When I started searching for examples of PBLs to wrap my head around, I found two problematic types: projects like “record a podcast episode to upload to YouTube,” which struck me as still very summarizing and lacking a truly authentic audience, or projects like “create a mural in the local community,” which would certainly require more time than I realistically had and, worse, be a one-time thing. Is a mural an awesome thing to do? Of course, but its better suited as an extra-curricular activity, in my opinion.

No teacher should pour their limited free time and energy into crafting unit after unit, year after year and each be one-and-done kinds of things. So, I’m definitely not going to recommend you do that. Your project needs to be authentic, but also sustainable.

After reflecting on the reason PBL-style teaching spoke to me in the first place—to tackle low civic literacy and engagement in our country—I gathered much more clarity and focus on those takeaways. It was then that project ideas appeared. Ones that would be very doable in a traditional classroom.

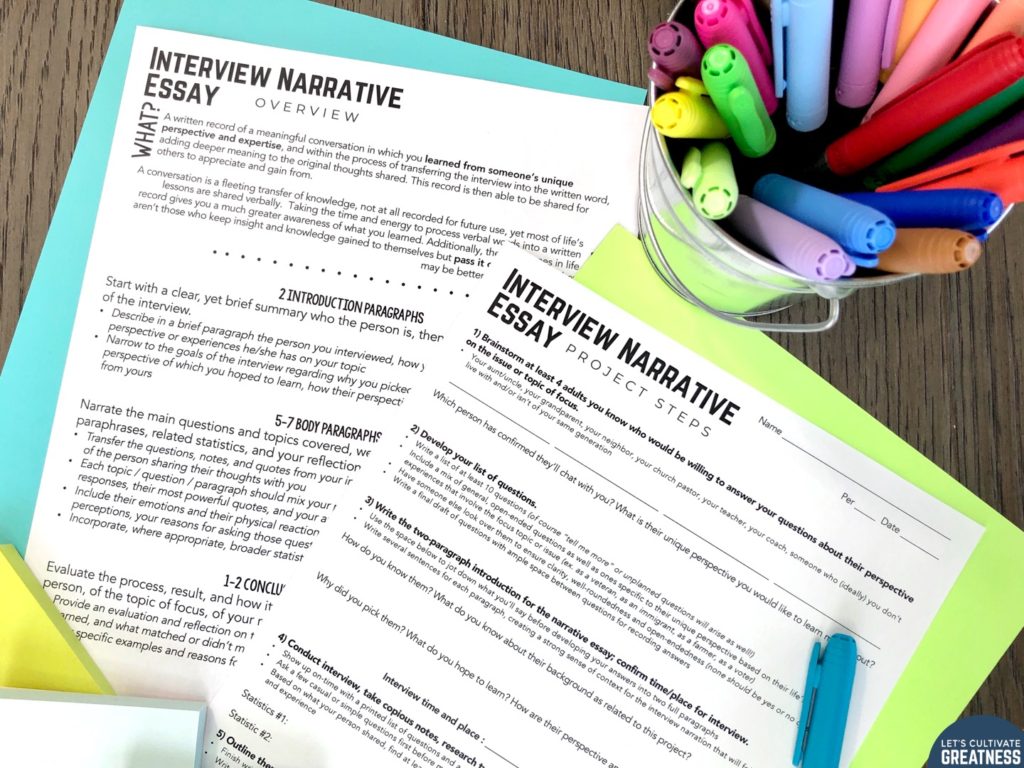

You could pair that novel study with a gratitude challenge and reflection essay. Or that geography unit with a National Parks Flat Stanley-esque letter writing experiment. And that history unit with an interview project where students ask an adult about the technology changes they’ve seen in their lifetime.

Interviews actually are my favorite PBLs because they are so universal. Check out this blog post where I detail the steps of how I weave this project into both my US History and Civics courses.

With these types of projects, students learn the core content of a unit you already made (yay!), but then immediately use that content and its takeaway to impact that larger world. And it’s repeatable year after year for you (double yay!).

Students develop a sense of empowerment and agency in a PBL classroom, and the tools to go do more great things in the real world. No brochure or collage project that gets tossed after it’s graded competes with that.

Question for you: What’s a takeaway you hope students are getting from your class, but don’t know for sure that they are?

Do PBLs have to replace the units I already have?

Textbook answer: Teaching a PBL unit doesn’t mean you have to throw out what you already do. It’s shifting how you are teaching that unit to make the project and student-led process central.

Been-there answer: You can totally still keep your lectures, activities, and end-of-unit test. I give you permission. Perhaps, though, you need to tweak your WWII home front lessons, though, to have a more overt, overarching theme among them.

As for the end-of-unit test, I still see a need for having “traditional” assessments alongside my projects. In a social studies classroom, there really isn’t any way around the fact that there will always be lots of content. Even with laser-focused driving questions.

I decided to keep a separate test when I realized that if the project itself was going to adequately assess all of the content, then it was going to wind up being be an inauthentic summarizing poster or presentation.

My students write DBQ-style essays to end each unit, after the project is complete. Our driving question is the basis for the essay and the project experience serves as one of the many “sources” students can use to support their arguments.

In my “Is voting an American right, responsibility, or privilege?” Elections & Voting unit, for example, our project is a mock election. Students write their essay citing the primary sources, current events, and activities we did, but they can also cite their experience of voting as evidence.

This allows students to be held accountable to the information in a more traditional capacity, and challenged to make real-world meaning with it through the project. And by writing argumentative essays, they strengthen college-ready writing skills.

Question for you: Which unit do you love, but get overwhelmed by trying to cover everything?

How much time do PBLs take?

Textbook answer: As much or as little as you want them to take. PBLs don’t have to be an “all or nothing” classroom format. This is a pedagogical shift, meaning content is re-prioritized rather than added to.

Been-there answer: If you’re confined to a tight scope and sequence with a laundry list of standards to meet, maybe the best time would be after the spring exam. If you have some flexibility, then perhaps working a PBL into one of your mid-year units to change up the routine, or you could commit to one per semester. Not every unit needs to be a PBL unit.

As for the actual project, it is only a portion of your time spent on the unit. Step one and two for my projects are always pretty easy—picking a topic and completing some preliminary work. They take just a portion of a class period to complete. Subsequent steps can take more time, but as long as they are started in class and accompanied with clear models and directions, students complete the rest as homework.

Also, remember that now your units are more curated, you have some more wiggle room for the project. For example, I don’t cover every tiny detail of the workings of the judicial branch, just what students need to know to understand the various influences that go into how case law defines our various rights. Certainly, that means we still cover a lot, just not everything. Remember depth over breadth.

Question for you: How much time do you already allot to a certain unit? What can you drop or tweak to make time for a project component instead?

What does a social studies PBL unit look like for real?

Textbook answer: A PBL should always have a driving question that is open-ended and creates curiosity and challenge, an authentic product for an authentic audience, and be aligned to standards.

Been-there answer: Yeah…that’s not a very satisfying answer is it? Between the moment I committed to the project-based learning approach and the moment I realized I was going to have to DIY the framework and the units myself, I searched high and low for concrete examples and step-by-step roadmaps. I couldn’t find anything, just general statements and general project ideas. Hopefully, I can do better for you.

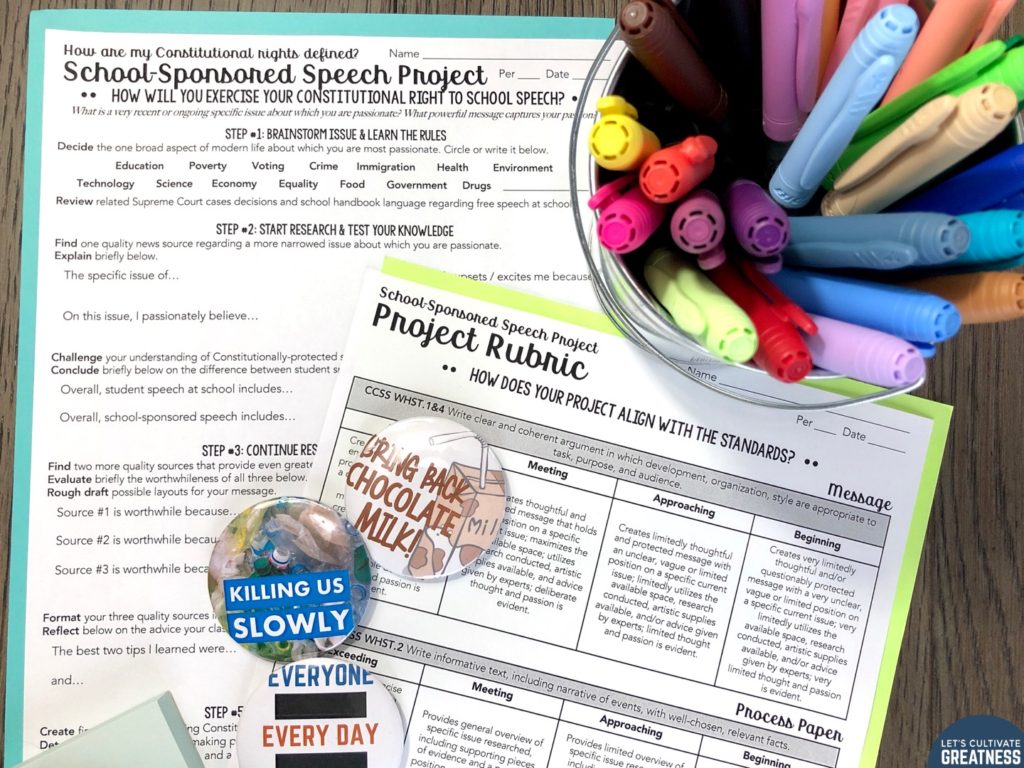

The following basic framework is what I follow when creating PBL units for my highs school US History and Civics classes. These are the questions I ask myself as I go through the planning process. I picked my Constitutional Rights unit, in which students create their very own free speech buttons, to serve as an example:

What is it about a topic or unit you teach that you want students to really know and carry with them into adulthood? How can that become an open-ended question that generates curiosity or a challenge?

When teaching about the Judicial Branch, I had always stressed how the nine individuals of the Supreme Court have incredible power to define what basic words in the Constitution mean and what they decide affects all sorts of daily life rights. So, I whittled it down to this basic inquiry: How exactly are my American rights defined?

What content do students need to know to answer that question?

This is where the editing process begins. What are the big subtopics? What already exists in your unit that works towards the answer? What needs to be cut? What needs to be tweaked?

I decided the exact details of the whole federal court system could go. I show a flow chart, talk about it for 5 minutes, refer back to it a few times, but that’s it. Instead, I now devote an entire lesson to the difference between the idea of strict and loose interpretation, because this idea is central to how a Justice will see a case before them. Plus, the debate of which approach is right (neither is!) is far more interesting than getting into the weeds of an inner-workings flow chart. And that exact debate is what makes Justice nominations so contentious and news-worthy, not how many district courts there are!

I have found 3-5 subtopics work great for a 4-6 week unit. For this unit, we cover the Framers’ intentions and Constitutional language, strict versus loose interpretation, the current Supreme Court justices, and a collection of landmark Supreme Court cases that outline basic free expression, privacy, equality, and criminal rights. That’s it, but we spend multiple class periods on each, going deep.

What is an authentic product students can create that culminates the content?

When you first start out, this will probably be the hardest part of the planning process, it was for me. As soon as I brainstormed the first couple of projects, though, it became a lot easier.

For this unit, my students create a political button they get to keep and wear. Even as seniors, they think this is so cool. The message and the design are entirely up to them, but the button must pass the free speech tests established by the federal courts.

This requires students to distinguish the nuances between free speech in different settings: on the street, in the hallways at school, and as part of a school project. Here, the students themselves as well as each other are the audience, but authentically so. Moreover, our principal, as their dress code enforcer, is also their audience.

Accompanying their button, students submit a process paper that outlines their research, rationale, and reflection.

In between each subtopic we cover, we complete one step of the project. This is where I divide up my projects into enumerated and explicit steps. First, it’s picking a current issue they’re passionate about and completing some preliminary research. Then, it’s diving into the specifics of free expression case law as related to student attire and school-sponsored speech. Thirdly, it’s conducting further research, deciding a position, and drafting up some button designs. Next, students collaborate to confirm their design meets the standards the courts have decided. Lastly, students make their buttons and write up their process in a short narrative.

I love this project because it’s so fun to see students wear their buttons on jackets and backpacks for the remainder of the school year! They are stoked to make something like this is as part of a school project.

I can’t praise the PBL approach enough for transforming my classroom and my energy for teaching history and civics. All the units and projects mentioned above are available for purchase in my store. If you are inspired to craft your own, send me a message! I’d love to help you build your first PBL unit!

Feature image credit: John Schnobrich