Analyzing primary sources actually means three separate things: reading, thinking, then writing. But we often talk about it and teach it as if it’s all a singular thing. It’s not.

Giving time to each of these three explicit steps means you are really treating it as the centerpiece of your history classroom because good analysis doesn’t happen in 5 minutes start to finish. In fact, it’s the expert historian who is never finished contemplating a source!

Of course we all know that in a fast-paced classroom it’s easy to lump them together, thinking students can move from comprehension to reflection to original writing in a handful of minutes… until we find ourselves grading student work that is simplistic and under-developed.

What happened?! We talked about this source with such detail. They seemed to get it!

As high school teachers, we can forget that the ability to articulate in concise writing is a different skill-set than talking open-endedly about ideas, and one that is still emerging in students.

The great news is that with structured sentence starter templates and models you can simultaneously teach high-level analysis and high-quality writing and do both in the short time you have.

Before we get started, let’s make sure you are in the right spot. The first two questions below make sure you have both a foundation of source analysis skills and know what good source analysis writing looks like. The last two tackle that in-between where people so often find themselves stuck —students have thoughtful insights and commentary while talking, but they aren’t translating it into their writing.

That, my teacher friend, is where simple sentence starters and models are like magic.

How do I teach primary source analysis?

If you are looking to build a strong foundation of in-depth reading, thinking, and talking about sources with your students, head over to this blog post where I detail my favorite, never-fail strategy for analyzing any historical primary source.

You’ll also want to grab my free Primary Sources Simplified Kit, a pdf download of 5 different analysis strategies to get your students thinking and talking about any primary source.

What exactly is source analysis writing?

It’s anywhere from a few sentences to a whole essay and is entirely dependent on the parameters you establish, which means you should have very clear outcomes.

One format I use often in my classroom is a paired source analysis format, in which we examine two short excerpts from opposing or related sources and have students produce a single, but dense, paragraph communicating their understanding of the two, what their position is on the central idea, and how the sources fit into the larger historical era.

I have a blog post where I give my step-by-step framework for teaching this type of source analysis using two documents. It’s the perfect way to practice DBQ skills before diving into a full-fledged essay.

But in order to produce a source analysis paragraph, students need an even smaller building block—the sentence.

It’s this step that we often skip, but then find students struggling to write those paragraphs. So, here are my best tips for teaching source analysis using sentence starters and models:

How do I teach source analysis writing?

No matter what kind of sentence template you are providing students, it should always have the following 5 components. Of course, this doesn’t mean high-level writing is rigid, because once students have a solid foundation, you should show them how to deviate from it!

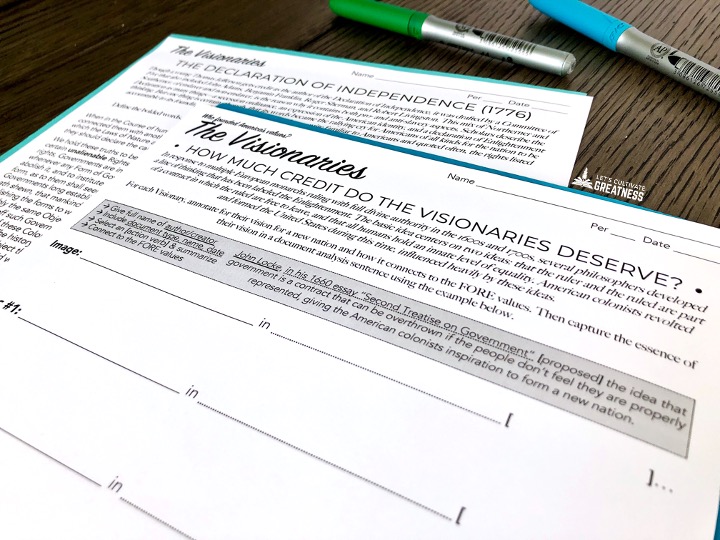

Below is an example from my first US History unit of the year, America’s Founding Values, in which we examine foundational documents. After discussing each source, students capture what they learned in a single sentence, connecting it to the values we are discussing. I like to list out these 5 components, as well as provide a model sentence right on the sheet.

1. Name the author/creator and any necessary identifiers like occupation or role in society.

For example, Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison… or Populist orator Marry Elizabeth Lease…

2. Name the source, type, and year published.

For example, Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, in his 1831 editorial essay,… or Populist orator Marry Elizabeth Lease, in her speech known as “Wall Street Owns This Country,”…

3. Pick an action verb.

After identifying the creator and source, lead with a strong verb—celebrate, agitate, warn. Having a word bank of verbs for students to access is definitely recommended.

4. Capture the essence of the source.

By this, I mean either include a short quote, a single fact, or a very brief summary that shows understanding of the whole source.

5. Connect the source to its historical era.

Tie the source back to the central idea of whatever was the point of reading the source in the first place. For example, the rising abolition movement as a moral argument, or the brewing division between Western farmers and Eastern industrialists. The easiest word to help prompt students to do this is which.

So, rounding out these two sample sentences, we have something like:

Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, in his 1831 debut issue of The Liberator, unapologetically demanded for the immediate end to slavery that kicked off a new era in the movement in which white Americans began a very vocal moral argument against the horrifying institution.

Populist orator Marry Elizabeth Lease, in her speech known as “Wall Street Owns This Country,” riled up audiences with her bold statements attacking the industrialized East, which contributed to the rise of the short-lived Populist Party that sought to give political voice to Western farmers.

What sentence starters should I teach for source analysis?

Kind of like a starter cookie dough recipe, the basic formula above creates a great out-the-door sentence that can be easily tweaked to accommodate different types of sources. I like to home in on certain types of repetition during a unit as we focus on different kinds of skills and sources, so I often have a source analysis sentence type to go with each of my units. Here are 3 to get you and your students going:

1. Visual sources.

This one is most like the starter formula above, but I challenge students to use rich adjectives in how they summarize and describe the visual.This is a great one to start the year with students.

{Artist’s name}, in his/her [work’s name, date, type], <strong verb> ~vivid description of image~ |connect to historical context|.

Photographer Dorothea Lange, in her famous image “Migrant Mother,” intimately captured the extreme wear, uncertainty, and stress that is so apparent in the worry lines and thread-bare clothes of one mother, symbolizing the great toll the Depression was having on families across the nation, particularly out West.

2. Quoted sources.

This is the type which students may be the most familiar from their English classes. Be sure to help students fight the urge to use long quotes—just a short phrase, sometimes even one word is enough.

{Author’s name}, in his/her [work’s name, date, type], <strong verb> ~quote~ |connect to historical context|.

A. Philip Randolph, in his 1942 essay “Why Should We March?”, presses the American people to commit to eradicating racial inequality with his “double-barreled thesis” that became known as the Double V campaign, in which African Americans pointed out the hypocrisy of fighting fascism abroad while oppressing millions at home during WWII.

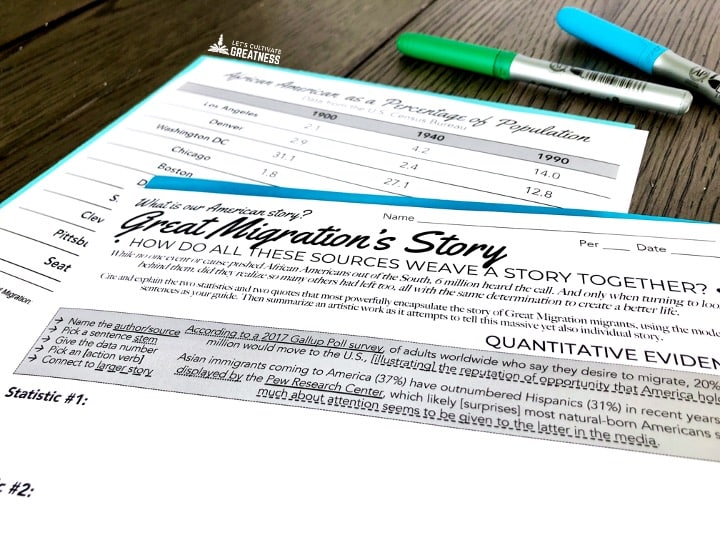

3. Statistical sources.

This one I use mostly in my Civics and other social studies classes, but I do incorporate it in my US History thematic unit on immigration to introduce this style of sourcing since it appears in the documentaries and secondary articles we examine.

According to {Source’s name}, in their [work’s name, date, type], ~statistic~ which <strong verb> |connect to historical context|.

According to a 2017 Gallup Poll survey of adults worldwide who say they desire to migrate, 20% or 147 million would move to the U.S., illustrating the reputation of opportunity that America holds.

These templates are not as rigid as they appear and the parts can be moved around as needed. However, the purpose of a template is to practice a new skill with few variables. Once it’s been mastered, then definitely show your students how to structure the same thinking a couple of different ways.

I always tell my students they are free to write something better than the template, but nothing worse.

Teaching writing often isn’t something we ourselves were taught how to do and students really do need more support than we think. I hope these sentence starters and models provide a solid foundation for you and your students.

If you want to learn more about creating a history or social studies classroom centered on source-based writing, check out my blog post on creating a DBQ classroom and grab my free kit of 5 primary source analysis strategies.

Feature image credit: Hannah Olinger