Essay writing is the one thing I felt the least prepared to teach when I become a social studies teacher. And by least, I mean not at all.

Early in my career, I attended the National Social Studies Council conference specifically looking for sessions on teaching writing. I was shocked to find hardly any.

Is it because we assume students know how to write by high school? Or because it’s regarded as such a fuzzy thing to teach that it’s unknowingly passed over in teacher ed programs and conferences? Or do we still think writing isn’t core to social studies the way it is to ELA? I have no idea.

That’s when I accepted that I was on my own to figure it out.

And it really should not be like that.

Over the years, I created and fine-tuned what I call a DBQ classroom, in which daily lessons build towards an overarching inquiry question and our end-of-unit essay answers it. In another blog post, I outline a broad overview of my DBQ classroom structure so if you’re interested in this approach, check that out before heading back here.

Whether it is US History, or Civics, or Global Issues, if it’s a core subject, I’m using an essay as the culminating assessment to answer the unit-long inquiry. I truly believe writing is that central to learning.

This post follows one I wrote on developing inquiry-based learning units and picks up where that one left off. That’s because these two core pedagogy elements—inquiry and writing—fundamentally belong together.

In this post, I will walk you through the step-by-step process of what “Outline Day” looks like in my classroom—when my students turn their general understanding about a topic into a precise, personalized, and well-supported argument. This is the second-to-last day of each unit, prior to “Essay Day.”

However, these same basic steps work for all types of history and social studies writing: end-of-unit essays, on-demand DBQs or LEQs, and formal research papers.

This is my 6-step how-to guide for scaffolding your history and social studies students in outlining an essay:

1. Deconstruct the essay prompt

2. Recap the truths, not just the content

3. Decide a clear position to argue

4. Choose categories to support a position

5. Select the best supporting evidence

1. Deconstruct the Essay Prompt

Don’t underestimated how crucial this step. Whether it is a unit inquiry question you wrote yourself or one provided for your curriculum, you must teach your students how to break it down.

Some questions to pose to students as you work through analyzing the prompt:

- What topics or content must I cover? What must I exclude?

- What’s considered true and not what I’m arguing?

- What skill must I demonstrate? How do I do that?

- What evaluation must I make?

If you want to go deeper on these 4 questions, check out my blog post on deconstructing social studies essay prompts step-by-step.

If this is a unit-long inquiry, then this deconstructing work happens early on and is also revisited throughout your unit. Personally, I never assign essays unless the question is known and understood all unit long, but sometimes you don’t have that ability.

If you’re preparing students for on-demand essays, like the AP Exam, develop a cheat sheet of your deconstructing system for students to follow. Then practice it with every essay.

One of the easiest and most heartbreaking traps I see AP students, even strong ones, fall into is arguing what the prompt already implies is true, missing the nuances of what the prompt was really asking, because they rushed this step.

2. Recap the Truths, Not Just the Content

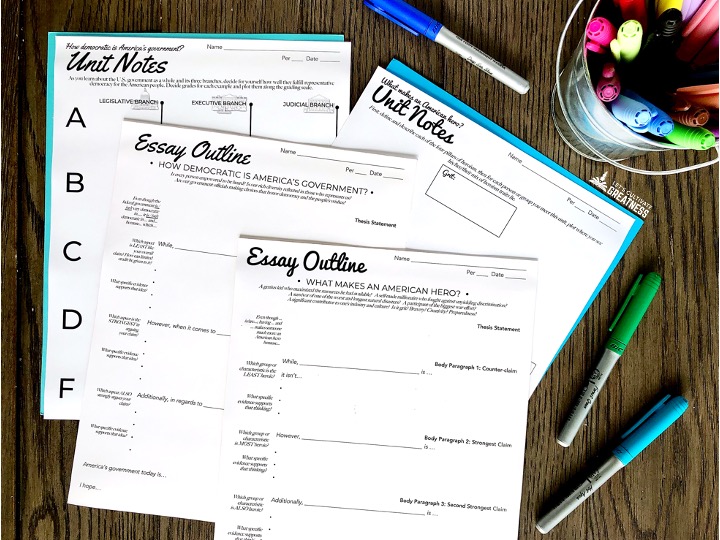

After it’s understood what the question is asking, now it’s time to review what it covers. If you created an inquiry unit with a central graphic organizer of at-a-glance notes and students have already loaded it up with what they’ve learned, you won’t need to spend too much time here.

Instead, focus this brief review time on the “truths” about the topic—the broad understandings about which historians, political scientists, and other experts generally agree. The first two deconstructing questions identified these things, so now it’s time to recap the details.

Keep it to 2-3 truths. Basically, you want to show that both or multiple sides of the question have support.

Continuing with our sample Gilded Age question from the last post on building an inquiry unit, “Was late 1800s America a land of opportunity?,” the core truths are that two things—unbelievable wealth as well as abject poverty—existed simultaneously. That is inarguable.

So review with students the most salient examples of both, one then the other. This scaffolds students in two ways. First, it prevents them from getting derailed by arguing that both existed equally, which honestly is just summarizing, because you have reminded students that this is already true and known.

Second, it reinforces everything they’ve learned in the visual of the graphic organizer. In our Gilded Age example we used a T-chart, but it could be a Venn diagram or a cause/effect flow chart depending on the question.

3. Decide a Clear Position to Argue

Pose the prompt once more. In big text on your screen.

And with their at-a-glance graphic organizer in their hands, students should now have a gut reaction answer. If not, they have their sheet to help them decide. Even if a lower-level student has just a few items listed, they can still decide one side or the other.

With our Gilded Age question, a student must either argue “yes” or “no” that late 1800s America was the land of opportunity. They can’t answer “both.” This crucial, fork-in-the-road decision prevents them from summarizing and sets them in a firm direction.

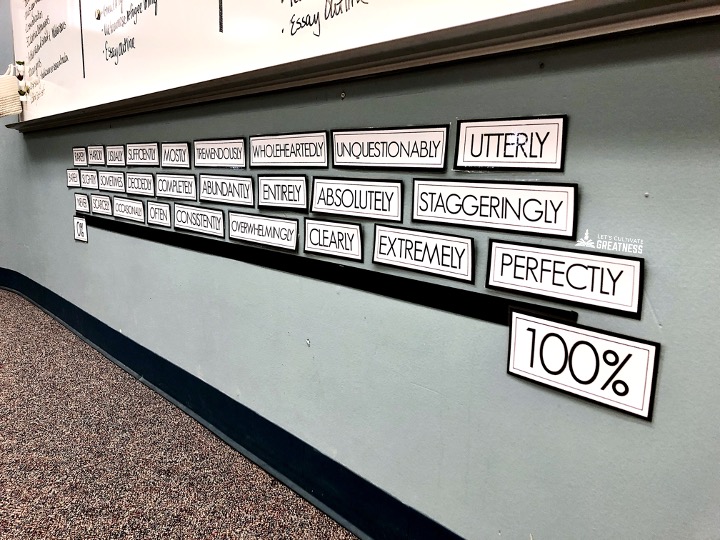

Next, students fine tune their decision into a more precise position. For most essay prompts, this is the argument qualifier—a single “how much so?” word that up-levels their writing significantly.

This continuum line of qualifier words on my classroom wall is my strongest tool to strengthen students’ writing and I have a whole blog post dedicated to how I use it daily, not only while essay outlining.

I have students write their two-word position on the top of their outline form—phrases like “somewhat yes” or “decidedly not.” This keeps them laser-focused and on-track, and from a quick across-the-table glance, I know so much about the argument they are forming.

I am a firm believer that good inquiry questions have unlimited right answers and that I’ve done my job well when distinctly different arguments are forming around the room.

4. Choose Categories to Support Position

After those couple of words are committed to their outline form, students now select their body paragraph categories.

The options of possible categories change with the question. Sometimes there’re only three options so everyone has the same three (though argued differently); sometimes there can be up to a dozen options.

To best support students, I suggest sharing a list of possible categories from which to pick. Of course, if students think of something not on the list, invite them to talk it out with you.

For our Gilded Age question, the categories could be groups of people, specific events, or even various popular ideas of the time. Lots of options depending on what you covered.

If you want students to include a counterclaim (and I highly recommend you do so!) in their essays, the clearest way to support them is by teaching it as its own paragraph. Meaning, if a student is arguing the late 1800s was a time of opportunity, their counterclaim paragraph might be on the plight of farmers.

After students label each body paragraph spot on their outline form with its category, I have them next write their topic sentences. Their thinking for choosing those topics is fresh in their mind and this clarity makes the next step even easier.

To recap, by this stage students have very little written in their outline form. Two words of position at the top and three body paragraph topic sentences. But the heavy thinking is done, and a clear path has been laid.

If a student is stuck or needs to talk out their thinking, it’s incredibly easy for me to glance at this uncluttered framework and immediately offer tailored support.

5. Select the Best Supporting Evidence

With precise topic sentences written, students now can much more easily select their evidence for each body paragraph. Provide space on your outline form for however many examples you want them to use.

With our Gilded Age prompt, if a student picked groups of people as their categories and choose the word “hopeful” in their paragraph topic sentence about the late 1800s “New” immigrants, then it’s easy for them to select pieces of evidence that best support that description.

This is another reason why having a unit-long graphic organizer is extremely important. Students already have the best evidence pulled aside and sorted into a T-chart, Venn diagram, or flowchart that directly supports the skill at the center of the question. Now it’s just a matter of curating the pieces that are relevant to the argument they are making.

If a student gets stuck finding examples, you can quickly glance at their topic sentence and point them to something that could work. This keeps them in control of their argument, making a kind of student-teacher synergy that’s almost magical. You’ll also see students use evidence in ways you never thought of.

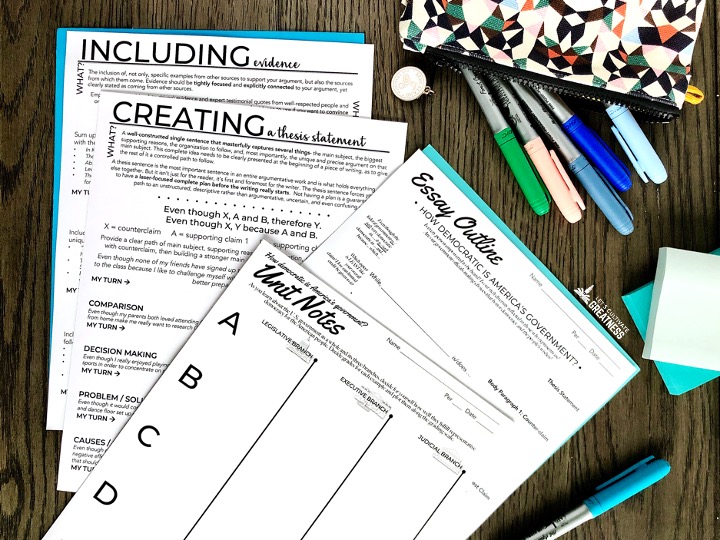

6. Write the Thesis

Ideally, you’ll have noticed that students are building their essay from the inside out. This order provides so much more accessibility to students at every level.

Since writing in social studies is the process of thinking, the thesis is much more the finale than the beginning. Strong and emerging writers alike benefit from this reversed approach, which also allows for better scaffolding through multiple micro decisions.

However, in the actual essay, yes, the thesis still goes at the beginning.

For years, I’ve used the Even though X, A and B, therefore Y formula with great success. X is the counterclaim paragraph, A and B are the two supporting body paragraphs, and Y includes the argument qualifier. I’ve never met a prompt this didn’t work beautifully to answer.

In my materials I pose a tailored version for students to build from. In our Gilded Age example, it would say, “Even though X was occurring during the late 1800s, A and B were more…, therefore America was/wasn’t <argument qualifier> the land of opportunity which…”

As much as we think formulaic writing isn’t what we want to teach students, we can’t ignore the fact that no formula at all is far more harmful. Strong and middle-leveled students naturally know how to build off of it and lower-level students know they can use every bit of the formula at no penalty. Trust that very few ever do.

After working through these 6 steps, students should have little issue writing a well-organized and well-supported essay.

Check out my US History, Civics, or Global Issues courses if you’re interested in making inquiry and essay writing central to your teaching. Both individual unit and full course options are available. Each unit includes all the essay writing supports you’ll need to scaffold writing like a pro—graphic organizers, outline forms, and how-to guides.

Feature image credit: via Pixabay